He is standing in front of you. You are commenting the weather forecast, he is agreeing, everything seems normal, but you know. You know that his mind is elsewhere. That while speaking to you, part of his brain is also fiddling with scores and notes. “ It can be dangerous you know. When I was a schoolboy, I would conduct while driving my bike. I’d imagine how to express and shape this or that phrase, use my hands to do so and wake up in a ravine.” Born in Hannover in 1964, Marc Albrecht is a German conductor, specialized in the late romantic repertoire. Big orchestras. Wagner, Mahler, Strauss, Korngold. For the past 10 years, he served as musical director of the Dutch National Opera and Netherlands Philharmonic in Amsterdam, appearing in parallel on international stages like the Scala in Milan, the Salzburg Festival, the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, the BBC Proms in London and the San Francisco Opera. Discreet and contained, Marc Albrecht doesn’t display any of the maestro’s flamboyant and mannered poses. His priorities are work and unification. “We both know, the orchestra and the conductor, that we are nothing without each other.”

When the Corona crisis kicked in, Albrecht found himself as many other musicians, deprived of his oxygen. Thrown to the ground. All performances canceled, an unsteady future lying ahead.” Maybe baroque orchestras will be the only ones to survive,” he says with a melancholic gaze. “You can spread the musicians along the stage. Squash people into planes and trains, evaporate them in concert halls. No more Mahler, no more Strauss, for a long time…Can I offer you a cup of tea?” By his side stands his partner, soprano Emilie Pictet, carrying a baby in her arms. “Marc spent most of his confinement in the church across the street. He is now considering becoming a professional organist.” Albrecht smiles. “I was indeed lucky to discover the organ, thanks, in a way, to the pandemic. It’s a fantastic instrument with countless combinations and possibilities. Like a big wind instrument, or even an orchestra. Hundreds of pipes, which each function like a voice.”

Marc Albrecht is without a doubt one of those. A bird or a fish who has been displaced on our dry earth. To reach back to his lost equilibrium he found music. A channel through which he can breathe, communicate and give meaning and purpose to his life. He concedes it’s an addiction. “When I entered adolescence, I realized I could no longer turn my back to music. It became a necessity, a condition of life.” His primary attraction to music seems however to have been stimulated by the desire to connect to a distant and inaccessible parent: his father, the conductor George Alexander Albrecht, who directed the Hannover State Opera for over 30 years. A man of undeniable qualities but whose authority would also induce fear and fascination among his family members. “Music was the only way to reach him,” admits Marc Albrecht. "But today we have great conversations. It’s a little bit like a game. And a partnership too.” Marc Albrecht’s younger sister, Julia is a musical agent who also manages Marc’s career. Their mother, Corinne Désirat was a ballet dancer who became a psychiatrist. Marc Albrecht and I met on sunny morning end of July in his apartment in West Berlin. The same day he flew to the Dolomites for a ten day hike. For him climbing and music share a few points in common, among which “the sensation of flying.”

***

How do you behave the day of a performance, do you have a certain routine to which you stick too?

My mornings are generally taken with rehearsals, sometimes even for different programs than the ones we will be performing in the evening. I try however to keep my afternoons free. Meaning no phone calls or appointments. Just the quietness I need to enter the tunnel. If necessary, I can reduce this important time to one hour or two, but I do need a moment where I can lie down, close my eyes and remain as calm as possible. It’s an energy thing. A low from which I then arise when the performance starts.

Can you speak when you are in the tunnel?

Yes. I can even play with the kids. The tunnel can occur in parallel.

And then?

I usually arrive quite early to the theater. Long before the public comes in. I go down into the pit or on stage, speak with some musicians who are already warming up. I like to slowly grasp the atmosphere, by talking, walking around, drinking a coffee. The Lampenfieber (stage-fright in English) starts when I change. The moment I put on my suit, it’s there. The real thing starts. That’s also why I tend to change as late as possible. Generally, not more than 10 minutes before the show. It does happen however, approximatively once a year, that when I change, the Lampenfieber, doesn’t come. And that’s a very bad sign. It means that I’ll go cold on stage.

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, 2018 © Marco Borggreve

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, 2018 © Marco Borggreve

How does a conductor communicate with an orchestra?

One is tempted to think that the way the conductor moves his or her arms and hands is what matters the most. I’d rather say it’s the eyes. In fact, one can conduct with one’s whole body, from the top of the head to the tip of the toes. The breath is also absolutely crucial. For the conductor’s aim is to transmit his or her musical ideal through one breath that is readable by all musicians.

Are there tricks one employs to bring this human mass to produce the sound you have in mind?

The sound the composer had in mind when he or she wrote the score is the basis to which we, conductors and orchestras are working towards. My job is to read and assimilate the music to the point of feeling I could have written the score myself. Then, every orchestra is different of course, has its own sound, spirit and tradition, so there is never one recipe. But I’d say that beyond any technique, the conductor’s mission is to unite. To gather everybody’s energy and focus around one idea. One wave. It’s like a Seifenblase, a soap bubble. To prevent it from bursting, it requires everybody’s care. If for some reason, we aren’t all focusing on this common objective – this one breath - we miss it.

When this Seifenblase moment occurs, how does it feel?

It’s like flying. Flying on the stream of sound. And it literally is. Because if you would ask me hold my arm in this position for 10 minutes, I’d soon be exhausted. Whereas at the end of a Wagner evening, where I had my hands up for approximatively five hours, I’m not tired at all.

Are singers part of the Seifenblase?

The singers enter the Seifenblase and are simultaneously carried by it. One can imagine the sound of the orchestra as a calm sea. A sea on which singers float upon without struggling.

Or without drowning?

It’s indeed very simple with Wagner, Strauss or any so called late romantic pieces to drown the singers with the sound of the orchestra. Ideally this huge orchestra force which is made of the 100 or 120 people should always remain aware that a voice is rising. If we want colors, it implies carrying the voice, which can also require at times to play much softer than what’s written in the score.

Do you often change the score?

I respect the instrumentation, which means I don’t change notes. I however do take the liberty to adjust, drastically, if needed the dynamics. To give you an example, a few years ago I was conducting Dar Wunder der Heliane by Korngold in the Deutsche Oper Berlin and ended up eliminating approximatively 570 sforzati to prevent the singers from drowning due to over-accented harsh playing of the orchestra. I love Korngold’s music so I had to help the score.

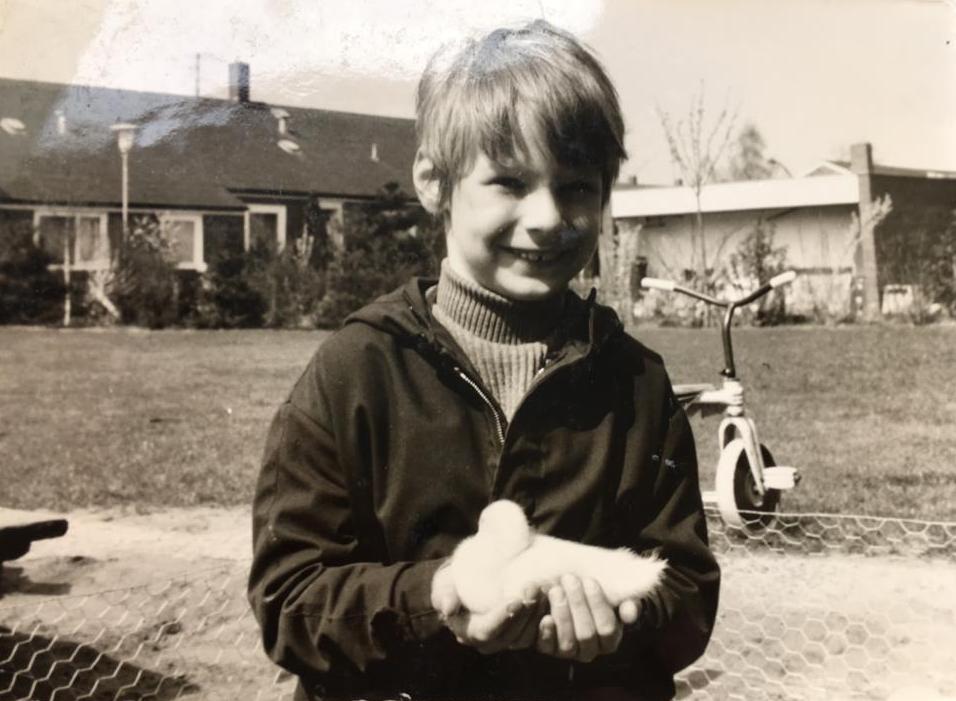

At age 8, in West-Germany

At age 8, in West-Germany

Can you tell us a few words about your childhood?

My childhood was very much constructed around my father and his work. His authority was unquestionable which meant that my sister and I were not allowed to fight with him or have discussions on critical terms or subjects. We more or less had to keep quiet at all times. During supper we were not allowed to talk and we had to walk slowly in the house not to disturb the concentration he needed to prepare his performances.

He was in his bubble?

Very much so and it’s something I didn’t understand nor like very much. I’m sure he needed it, to protect himself. And as a matter of fact, when I turned 12 or 13, I’d behave exactly like him. I would lock myself in a room and ask everyone to remain silent because I needed to work on the piano. But today I try to act differently. I do my best to bring this bubble of concentration down to the moment supreme, where it really counts, during the preparation, rehearsals and of course during performances. I don’t think the podium should be used outside of its technical function, at the kitchen table, in the streets or on the tramway. It doesn’t bring anything to the music! Luckily things are changing for the better today and many conductors try to behave normally.

When did you start your musical training?

When I turned 5, my father suggested I start learning to play the violin. He was a great violinist before becoming a conductor. So in his very tight agenda, every day, at the same hour in the afternoon, he would open his office door and say, “Marc, it’s time for our half hour of practice.” I love the sound of the violin, but it takes ages to arrive at a bearable sound. And I don’t think parents are always the best teachers for their children. Too many implications. Anyhow, for a year, my father tried to show me how to get to this sound, but results remained disappointing. So I ended up, at 6, switching to the piano. And that’s when things opened up for me. My father wasn’t so talented at the piano, which meant that from that day on, the piano became my own instrument. My space.

When did you switch from piano to conducting?

Conducting came naturally to me. When I was 16, I was leading the school choir and an instrumental group. In parallel I was also in a brass band where I played the trombone. It was basically a wind orchestra. One day the conductor fell sick and I stepped in. I suddenly felt it was possible to make a group of musicians and singers follow my gestures and ideas. I then became the second conductor of this orchestra and I guess that’s when everything began.

Did you ever think of turning your back to music and do something radically different?

I briefly examined the possibility of studying medicine, but it never overtook my aspiration for music. Most kids drop their instruments at 12 or 13. For me it was the opposite. That’s when music became a necessity, a life condition. I felt I had to preserve its energy and do everything not to lose it. Back then, I was really infected by Wagner’s music. I had entire performances playing in my head. I’d lock the door of the living room, sit at the piano and start playing, let’s say Tristan’s first act, and I wouldn’t stop once for 75 minutes, I’d play, sing all the roles, imagine the scenes and actions on stage. It must have sounded weird! That’s also when my father started his Ring project in Hannover and when I became a rather irregular student at school. I didn’t want to miss one important rehearsal of this incredibly exciting music. I later did the same with his Mahler and Bruckner symphonies. My father and I would also play them together on the piano, with four hands. So, I guess that when I could have turned my back to music is when music became stronger than anything else.

So you never took a break?

Well, I did my civil service, which lasted 18 months. My father wanted me to enter the military band as a trombone player, which meant doing very little and having time to remain focused on my studies. I would have followed his advice if it didn’t imply going through the military training which consisted of learning how to kill people. We had many discussions around this issue. Yet, I ended up opting for civil service. I worked in a psychiatric hospital in Hannover with the idea of continuing my studies in parallel, but my days were exhausting. I’d manage in the evening to work two hours on the piano but not more. Nevertheless, I keep a fond memory of this period. As indeed everything went very quickly for me in one direction. So to be obliged to suddenly stop, to help people in trouble and to access this world of locked doors was an extremely gratifying experience for me. It enabled me to see another side of the world.

Before going back to your side of the world, namely to Vienna where you become Claudio Abbado’s assistant?

Yes, I was studying at the music academy in Vienna and I was a little bored. Luckily, I managed to find a job as a pianist for the Studio of the Staat opera of Vienna. And since I was a staff pianist, I could access all the rehearsals. Abbado was just starting there as music director in the house and one thing led to the next.

What did he teach you?

He never gave me any lessons. He hated teaching. But I was absolutely fascinated by his art and personality and that was largely sufficient. He was a maestro but wouldn’t show it all the time. He didn’t need to construct it. He was a very accessible man, easy to talk to and you could see this on the podium. The way he communicated with the orchestra was really unique.

Valais, Switzerland, 2019

Valais, Switzerland, 2019

How do you cope with the measures enforced by the corona crisis which prevents normal performances from occurring?

With difficulty. It’s as if I was waiting for a 1000m race to begin whereas there are no more races. Corona brought me the sensation of suddenly having my entire system put on hold. I miss music tremendously and also the energy I retrieve from working and interacting every day with people. Fortunately, after a few painful weeks at the beginning of the confinement, I managed to find a way out of this depression: as always through music. Music as a salvation and a therapy. I went back to my piano, which I practice everyday and which enables me to continue expressing myself. And I also discovered the organ. An instrument I would have probably never played without the crisis. That’s what is great with music. You can find it everywhere. If I can’t perform, I just cross the street and go practice the organ in the nearby church.

If you could reincarnate and chose the country, century and profession?

I’d come back as a free climber. Someone who climbs mountains without any rope, like Alexander Huber.

What do you like so much about climbing?

Only using your hands and feet to arrive to this verticality has something reminiscent of flying. Of overcoming gravity. Of course, I use a rope. But I find these guys who can rely on their strength because they know they can do it, absolutely fantastic.

If you were a philanthropic billionaire to which cause would you give out some of your money?

I’d set up a foundation to ease the unbearable living conditions in the refugee camps in the Aegean.

***