He wrote more than twenty books, heads the homeopathic research and clinical training Academy The Other Song, leads the holistic healing retreat Sampoornam, owns and directs HMP, a homeopathic publishing house, as well as Synergy, a computer software used by most professional homeopaths, works in his own clinic, teaches, travels, spends plenty of time with his family and friends, sings, laughs and, worst of all, constantly seems totally relaxed. When I asked him what his secret was and how he managed to be so prolific he answered, "I guess I know how to delegate."

Born in 1960, in Bombay, Rajan Sankaran is an Indian doctor and homeopath known as the father of the “sensation method,” an approach based on matching one’s subjectivity to a remedy. Disease is considered to be an expression of a non-human pattern or song, that belongs either to the animal, plant, or mineral kingdom and that seems to be rooted in our minds and bodies. This otherness in us doesn’t only influence the way we experience and express symptoms, but also the way we dream, love, hate, think, play, sleep, eat, and so on.

For those who are unfamiliar with homeopathy, the theory is based on similarity and sameness. "Like cures like". Nut allergies are healed with nuts, night terrors with substances that induce night terrors. The idea is that the energy of the given similar triggers or resets the patient’s immunity which then harmonizes (heals) the dissonances (diseases). Modern medicine, on the other hand, functions mainly through opposition (heat being treated with cold), extermination (removal of the sick tissues or organs), and oppression (antibiotics, corticoids). This exclusion or distancing of the otherness within leads towards normalization (e.g eternal youth and productivity) and not, as in homeopathy towards the celebration and potentializing of the diversity within.

Homeopathy moreover echoes many contemporary philosophical ideas – such as Bruno Latour’s “landing on earth,” or Achille Mbembe’s “in-commonness” about ways for us humans to re-integrate and re-harmonize our existence with the environment. Perhaps even more so than a healing method, homeopathy is also an art de vivre, one in which every single element and organism inhabiting our planet has a role to play. When one of these elements or organisms is violated, when its beingness is unable to express its purpose or sound, diseases occur, affecting, in turn, the entire “circle of life” and thus, our co-immunity.

To come back to Rajan Sankaran, he is considered in today’s homeopathic realm to be some kind of god or king. I met him in person once, and only briefly. It was a few years ago, in Gloucestershire. He had been invited by The School of Homeopathy to give a conference. A tent had been erected for the purpose of his visit and students and homeopaths from all over Europe had gathered quasi religiously to listen and witness the art of Rajan Sankaran. He arrived on stage a few minutes late, totally relaxed, reviewed a few cases – including one in which he helped an old woman in the final stage of cancer ( her metastases had magically reduced in less than 6 months), marketed some of his recent products, made some jokes (which I reckon were hilarious) sang a song, thanked his audience and disappeared.

The present interview was recorded in April 2021 by zoom. He was in Bombay, I in Salzburg.

***

Homeopathy was invented in Germany in 1796. Today its practice is marginalized in the West and celebrated in India. How did this happen?

Homeopathy was popular in the UK in the 19th century and arrived in India through the British Colonies, namely in Calcutta that back in the day was the intellectual capital of the country. It rapidly gained huge success among Indians to the point that the British Medical Association decided to forbid its practice. To do so, they sent to Calcutta their vice-president, Dr. Mahendralal Sarkar, with the task of denouncing the fraudulence of homeopathy. When he arrived in Calcutta, he visited a homeopathic clinic and was so impressed by its results that he ended up giving a speech in which he claimed homeopathy to be the medicine of the future. Dr. Sarkar was then of course immediately expelled from the British Medical Association. Nevertheless, his intervention had a positive impact on the development of homeopathy in India. Today, India is the only country in the world that includes homeopathy in its medical system. Medical students follow the same courses before specializing either in allopathic, Ayurvedic, or homeopathic medicine. Homeopaths, therefore, benefit from the same rights and privileges as any other conventional Indian doctor.

In his clinic in 1990, Bombay

In his clinic in 1990, Bombay

Are there other reasons that explain why homeopathy continued developing in India whilst being practically extinct elsewhere in the world?

There are a few, yes. One is that most Indians are not very rich and can’t afford modern medicine. Yet, the upper class, politicians, movie stars, and so on, also turn to homeopathy simply because modern medicine has no solution to cure chronic diseases. Allopathic medicine focuses on a delimited organ or part of the body to treat one particular symptom, whereas most diseases result from an immune deficiency. Asthma might manifest itself in the lungs, sinusitis in the sinuses, they remain immune-system problems. If you have rheumatoid arthritis, you can for sure see a rheumatologist. He might be able to temporarily relieve your symptoms, but he most probably won’t have any long-lasting solution.

Why?

Because rheumatoid arthritis isn’t a disease of the joints but a disease of the immunity! An immunity that is itself part of a system that is influenced by our mind, hormones, and nerves that can only be reached if the person is treated as a whole.

Are Indians more inclined to see the picture or patient as a whole, than Westerners who tend to focus on isolated details and symptoms?

India is ruled by two fundamental philosophies. The first is that if I’m right it doesn’t mean that you are wrong. And the second is that if you are right, it doesn’t mean that I’m wrong. Most modern doctors in India respect alternative and holistic approaches, whether it be yoga, Ayurveda, or homeopathy, precisely because they don’t embody a “you versus me” position. They collaborate with various methods in the patient’s interest. To give you an example, I'm now collaborating with an oncologist surgeon specialised in breast cancer. Being regularly confronted with granulomatous mastitis, a condition that mimics cancer but that isn’t one, he started referring his patients to a homeopath who has, as of today, already successfully treated more than a hundred patients suffering from granulomatous mastitis. We are now conducting together a systematic research on the effectiveness of homeopathy to heal this condition.

With actress Gracy Singh during The Other Song's fifth anniversary

With actress Gracy Singh during The Other Song's fifth anniversary

©Anusha Srinivasan Iyer

Why do we, in the West, embody this “you versus me attitude”?

I don’t know why Western people adopt this “if I’m right you are wrong" attitude that also implies that because I cannot be wrong, I have to prove to the other that he can only be wrong. The Western world has a strong desire to finish anything that doesn’t match with its own vision. You just need to see how western media and politics work on endlessly bashing and humiliating homeopathy. Why would somebody object to a medicine that is harmless and anyway considered by its opponents as ineffective? If someone wants to treat himself with homeopathy, why go against and ridicule his choice?

Why?

It’s difficult to understand why. Some people suspect that there are some commercial interests coming namely from pharmaceutical companies. And it’s true that each time a clinical trial is conducted in homeopathy it somehow, for one reason or another, ends up being discredited for motives that are held to be scientific, but that are, in reality, political. The common sense would be to lead scientific studies together as we are for instance, accomplishing right now with the oncologist I mentioned above. Homeopaths are open for collaborations. The resistance lies, I believe, elsewhere.

How do Indians deal with their colonial past?

I’d say most Indians are through with this part of our history. Nobody talks about it nor blames anyone for it anymore. Unfortunately, most of our politics have created a bigger mess than the British ever did.

Isn’t there a desire for reparation or at least a sentiment of having been mistreated by the West?

Nobody blames the British, not one single person. What I saying, is that most people in India prefer to leave the past to history and focus on the present situation.

What’s your understanding of victimization? Is it an emotion or action that can have positive or healing effects?

If I’m totally honest, I’d say victimization is an unhealthy attitude. The moment one points out somebody else and says, “he over there is the father of all my problems,” he avoids becoming aware of his own self. I guess my inspiration here remains Gandhi. He maintained to have nothing against the British, to love them as every other human being and soul. Yet, he felt their policies and imperialism weren’t fair, that no one should be ruling over another in this manner and that therefore he would find a solution to make this stop. His answer didn’t come from the desire for revenge and the urge to kill the British but from a place of acceptance and awareness.

Don’t you think blood is sometimes necessary to lead a revolution?

Awareness doesn’t mean being inactive. On the contrary, it stimulates one to take steps in a productive and constructive manner by understanding where the other person is coming from and why he is acting the way he is acting. Acceptance and awareness push one to organize oneself in accordance with a situation that is felt to be unfair. It can require one to protest, but not out of hatred or victimization. Hatred and victimization remain perceptions; they aren’t the truth. To go back to Gandhi, he understood that to dislodge the British from India, one had to cut their income. He namely invited the Indians to make their fabric at home because the British were making money by selling them cloths. He was looking for peaceful ways to stop cooperating with the British. Non-cooperation is in my opinion way more effective than hatred, revenge, and victimization. What continues to make me laugh today is how the British built a statue for Gandhi in London (laughter). Can you imagine the dynamics which led them to erect a statue of the man who destroyed their empire?

Music lessons, Rajan Sankaran on the right end of the bed

Music lessons, Rajan Sankaran on the right end of the bed

How did you arrive at homeopathy?

My father was a conventional doctor. He got very sick, modern medicine couldn’t help him. He went to see a homeopath who healed him and from then on he decided to devote the rest of his life to homeopathy. He traveled around the world to learn and teach and yes, I was very impressed by him.

You are considered to be the father of the sensation method, sometimes referred as the Bombay school of homeopathy. What’s the difference between your method and classical homeopathy?

Homeopathy is traditionally based on matching one patient’s symptoms to the symptoms of various remedies. This has been going on for 150 years and achieves very good results. In the sensation method, symptoms are also considered as expressions of the patient’s internal experience of reality. They are therefore used as channels to observe something that lies behind the symptom. By studying my patients’ various perceptions of reality, I discovered patterns, that can be linked to the animal, plant or mineral kingdom. Moreover, within each of these kingdoms, we find group qualities that are for instance specific to the mammals, the birds, insects, reptiles and so forth. Recognizing these patterns and group qualities is therefore just another tool to enhance your chances in finding your patient’s corresponding remedy.

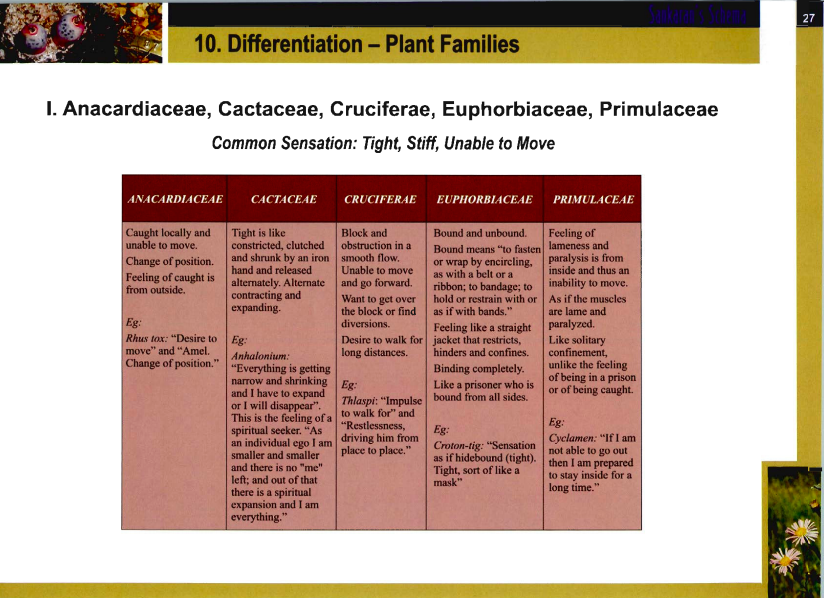

Key-notes on common family plant sensations

Key-notes on common family plant sensations

Excerpt of Sankaran's Schema 2005

Do we all possess something that belongs to the outside world and that isn’t properly human?

We certainly all have something of everything in us. Yet, each individual is stuck to a particular melody that is linked to and echoes something else in the universe – an animal, a mineral, or a plant. Those who are influenced by an animal energy for example tend to be competitive and survival-oriented. Plants generally function through sensitivity and reactivity and minerals hold a theme of lacking or losing something. One rarely remains blocked into one pattern or remedy. In my practice, at least, I’ve never had a patient who stuck to one kingdom.

Homeopathy isn't considered to be an evidence-based medecine and is therefore rejected, namely in the West. It moreover employs energetic remedies that no longer contain any molecules. How can one defend the invisible?

There are two types of research. One focuses on the physicality of the substance. Is there something or is there nothing? Quantum physics works on nanoparticles and the memory of the water and numerous theories have been advanced in this department. Yet, in my opinion, one shouldn’t lose time with this part of the research, because we may never understand how homeopathy works. The question shouldn’t be “how does it work” but rather “does it work?” To do so, we need rigorous double-blinded clinical trials. That is to take one disease, let’s say hypothyroidism or granulomatous mastitis, and treat 150 people with traditional medicine or placebos and another 150 with homeopathy. The results will for sure be favorable. My plan is actually to devote the next two to three years of my life to double-blinded clinical trials. It’s the only way we have to convince western medicine to start looking into homeopathy.

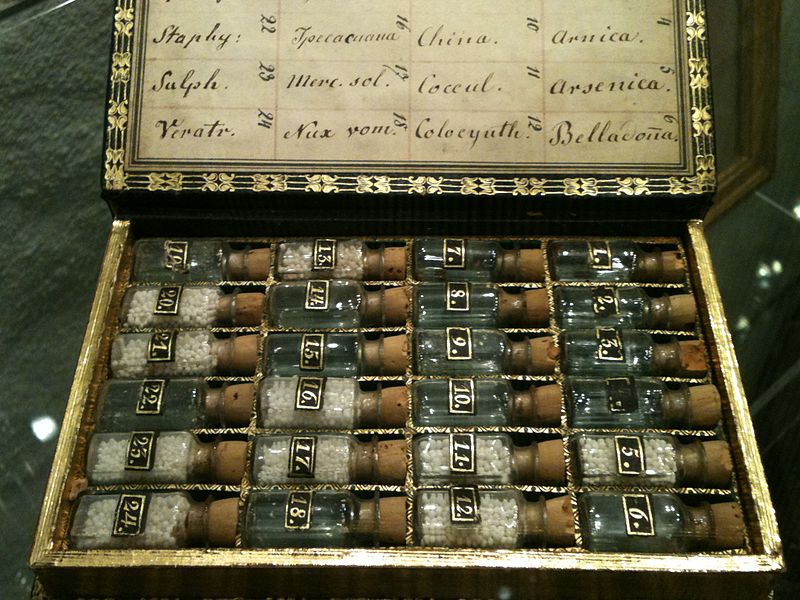

Remedies used by the founder of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, in 1842 in Paris

Remedies used by the founder of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, in 1842 in Paris

© Apothekenmuseum, Heidelberg

Could homeopathy die?

Homeopathy has already been through several ups and downs, and it never died. After the second world war, it was practically extinct. In the 1980s, it experienced a revival and now, it’s again going through a decline in the Western world. If homeopathy is still evolving today, it’s for a reason. Though it lacks sufficient clinical trials, enough people have witnessed and experienced its effects. You know, the truth always survives.

If you were a philanthropic billionaire, into which cause would you throw your money?

I’d give it all to animals and to the wildlife we are destroying in the most disgraceful manner, jailing animals in zoos, cutting their skins, killing them for ivory – do you know how many wild tigers are left? Do you know how many beautiful creatures will be extinct in one or two generations?

They will survive in zoos.

Yes, zoos or extinction. My heart goes out to them you know. Animals have no voice and we need to protect them. So yes, if you ask me where I’d put all my billions, it would be in creating awareness for these animals.

Which particular animals touch or echo with you the most?

Tigers, elephants, lions. But my billions would focus first on all the animals that are threatened with extinction.

Are you vegetarian?

I’m vegan. I don’t use any animal products, no leather, no silk, nothing that comes from an animal. I still can’t fully wrap my head around the way we produce silk – meaning by putting live creatures in boiling water. We are exploiting animals beyond imagination, killing them for please and luxury, cutting them to use their leather…

Is it less acceptable than cutting trees?

Yes, you are right, but somehow animals are more like us. Even though they can’t speak, you can feel and relate to their emotions. Trees also need to survive, sure. I guess our aim should be to take the least possible away from the earth, to use its resources to the minimum, and maybe, why not, planting a new tree for every tree we take away.

If you could reincarnate, where, when, and in what would you choose to come back?

I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else except where I am right now. This is the place I have been given by the universe to evolve and learn. I can’t take somebody else’s course.

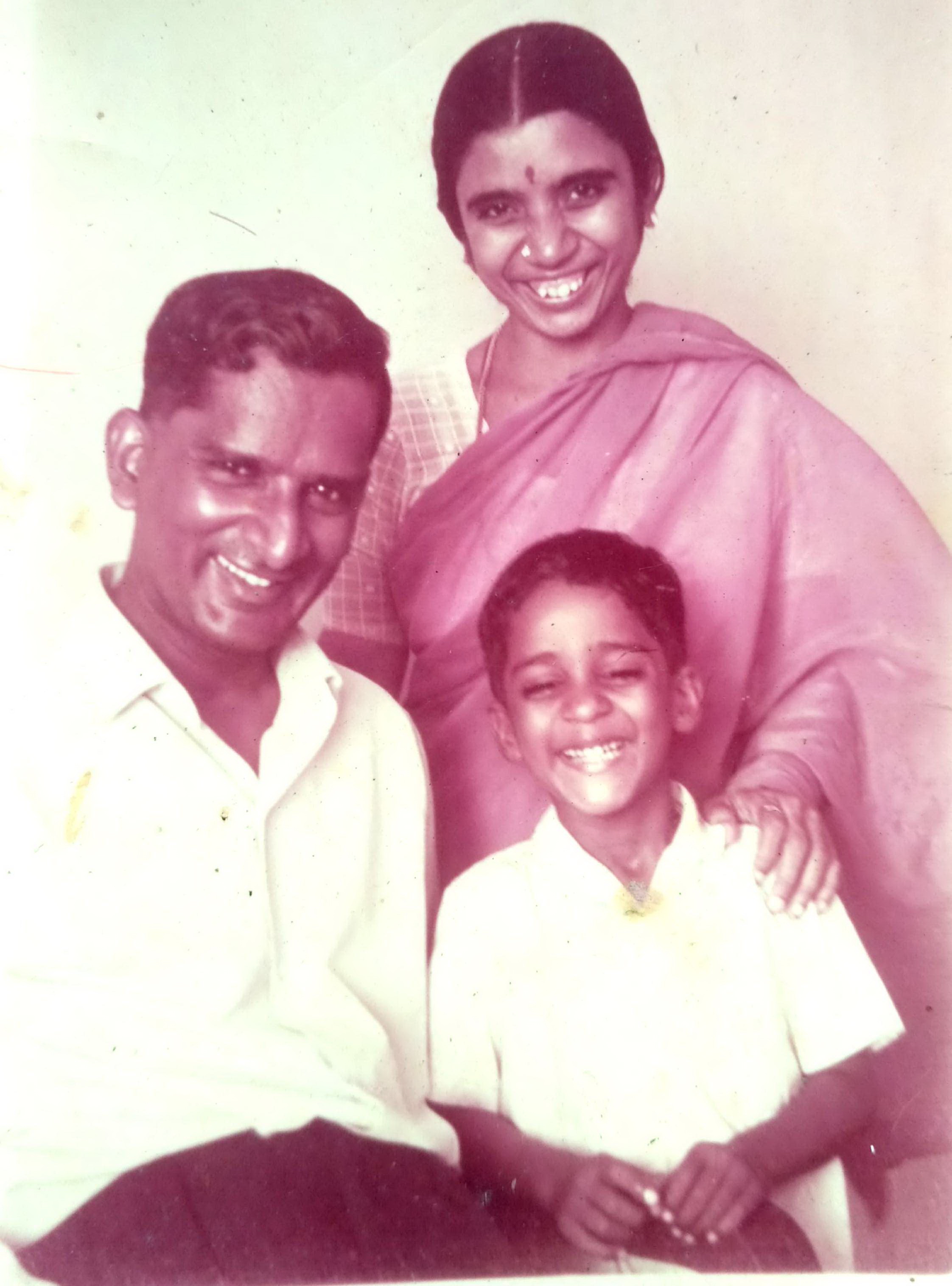

With his parents

With his parents

Suppose a gun is pointed at your head and you have to choose?

Then I’d choose to live next to a spiritual person. An enlightened master such as Ramana for instance who lived in Southern India. I’d like to devote myself to the service of a guru or spiritual master.

To be a servant rather than a master?

Yes. The moments I have spend with such enlightened beings have been the most meaningful of my life. I actually refer to them in my book, Dog, Yogi, Banyan Tree.

What is a spiritual master?

Someone who has dissolved his ego completely and who has become one with the universe. This means that his individual being almost no longer exists. He has become an instrument of the universe, even though he remains fully conscious. When you are in the presence of such a person, your mind automatically calms down and brings you towards experiencing an egoless state.

Should this egoless state be the goal of each one of us?

If it’s a conscious goal it means it’s coming from your ego. If it’s a natural progression, meaning a state where you realize that you have had enough of this world, that you have achieved all that you could still possibly desire, let it be fame, money, or good friends, and that you realize that something is still lacking, that all this doesn’t bring you peace, then you might enter a state in which your ego will naturally dissolve.

One could also just kill oneself?

In one’s conscious life there is joy to be found, I believe, in a space that lies behind the constant thinking, feeling and emotions that drive our ego. It’s the spiritual space, the one of beingness, consciousness, and awareness. This space isn’t you, it isn’t you being in that space but only a beingness. One that is beyond birth and death and where it no longer matters if you are in your body, or not. For your beingness is evolving in a wider context. It’s the consciousness that you are nothing and yet everything. And when you reach this state, you fulfill your potential on earth. This potential is what you have to give. The apple tree’s potential is to give apples, the river’s is to give water and each one of us is inhabited by a potential that can only be fully accomplished once the ego disappears and the universe acts through your beingness. We are also here, as each individual, to give something. However, because of our egos, we think that we are here to take something, to grab or pull something out of somebody else, but that never leads us to happiness – happiness is when we achieve a state where we are natural givers and full of love.

***