Interviewing Johannesburg-based Xhosa artist Nicholas Batandwa Hlobo is as challenging as carrying water without a vessel. Eloquent and full of sharp metaphysical considerations, he continuously slides away, adding new layers to his answers and beliefs. Born in Cape Town in 1975, Hlobo spent his childhood in Dutywa, on the Eastern Cape, before moving to Johannesburg as a teenager. Today in his forties, Hlobo is a key figure of the city’s rising cultural scene, one that is reminiscent of the golden ages of New York, when artists would hold ateliers in old factories in downtown Manhattan. We met on a sunny September afternoon, in his studio, located in a vast and beautiful old synagogue in Lorentzville. A young man resembling Hlobo opened the gate to let me in. He served me fruits and a Ceylon tea with honey. It’s only when Hlobo arrived that I understood he wasn’t the real Hlobo but his assistant. “You met my younger self” said the real Hlobo with a grin. He then lit himself a cigarette.

Worried about committing a faux-pas, I immediately inquired on the apartheid name of the Transkei, which designates part of the land where Xhosa people live and where Hlobo grew up. Can one still say the Transkei or should one use another term? I asked. Hlobo set aside his cigarette and told me he was against these constant name changes, as they contribute to erasing memory. In his opinion one shouldn’t hide or condemn but reveal and celebrate. His creative process is one of juxtaposition and layers and incorporates various materials such as ribbon, copper, wood, leather, rubber and found objects. Exploring several means of expression, Hlobo paints, sews, sculpts and performs.

From 2010 to 2011, he worked for artist Anish Kapoor, who immediately considered him as his talented protégée. Endowed with an overflowing curiosity, his knowledge ranges from Rudolf Steiner to international geopolitics. Whilst discussing with him, I was subjugated, not to say devitalised, by his self-confidence. Hlobo's trust in himself seems unbreakable, and this may perhaps partly explain why he never experienced creative blockages or doubt. To put it differently, Hlobo knows where he is going, what he is doing and more importantly, who he is.

***

Your grandmother played an important role in your upbringing, could you tell us more?

As it often happens in our culture, I was raised by my grandmother. She was more of a mother to me than my actual mother. Though she died in 1995, I continue to be intrigued by her today. She was a rebel and most probably a feminist. She separated from her husband, which was very unusual at the time, took a piece of land in another village and lived there on her own with her children. She used to tell my cousin and I, “Men make you pregnant and then they leave.” She insisted that we learn how to rely on ourselves. She would tell us, “Kids, you are born in our family, we can show you the path, but you will always be alone in life.” She was very strict and at the time I didn’t like her so much. Now, of course, I’m grateful for everything she did for us. My values of wisdom and love come from her. My grandmother would have wanted to go to school, but circumstances were not in her favor. She didn’t know how to read nor write and obliged us to go to school nonetheless. She didn’t want us to hate her for having deprived us of this opportunity. Yet, she didn’t like the Western concept of education. With time she came to realize that school changes you. The minute you enroll in its system, you cease to be Xhosa and you become someone else. Whereas for my grandmother, the most important thing in life is to be yourself.

Did you inherit or practice any traditional Xhosa rituals?

I got baptized in a Christian church and was simultaneously made an imbeleko. An imbeleko is a cradle that is conceived out of the skin of a goat or sheep that has been slaughtered to introduce you to the spiritual world. It has similarities to the Christening of a child in a church. During this ritual, the baby is the first to taste the meat. If he is too young to eat the meat, he licks a piece and his or her mother eats the rest on his or her behalf. I was also given two names. Nicholas and Batandwa. Batandwa means ‘beloved’ or ‘beloved people’ in Xhosa. It comes from “Bathandwa BeNkosi,” which refers to the way people address themselves to the bible.

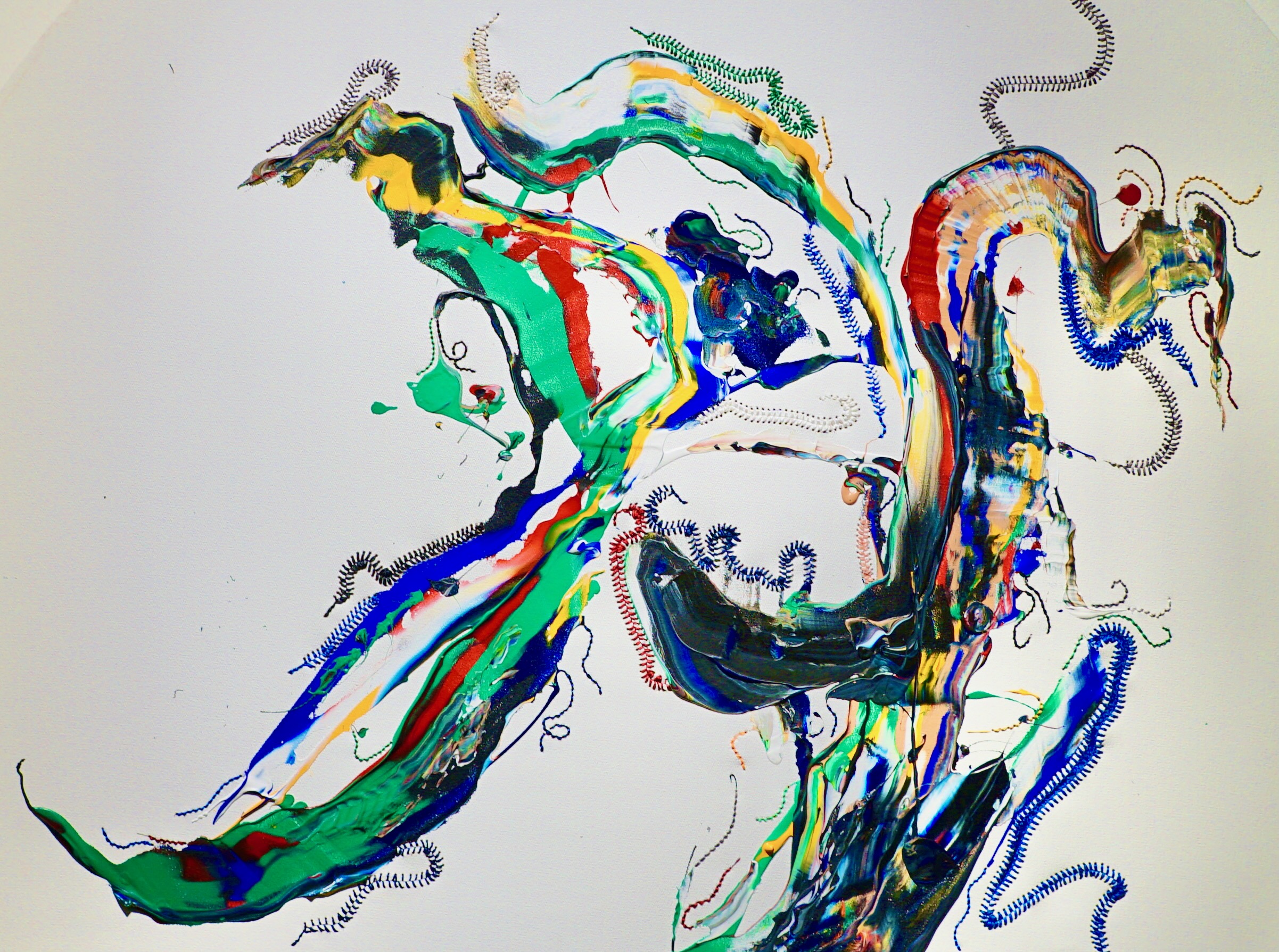

In studio, Lorentzville, Johannesburg, 2022

In studio, Lorentzville, Johannesburg, 2022

How and when did you become an artist?

As a child, I would kill time by drawing. I’d draw at home, or on the sand while waiting for the queue at the communal tap to shrink. I’d focus on the human body, but as it appeared in my imagination. I then went to art school in Johannesburg with the ambition of working in the film industry. I also wanted to become a musician and a designer. Yet, my focus brought me to image-making and that’s how I became an artist.

Which musicians to you worship most?

So many. I love Bjork. I like the strangeness of Sigur Ross and how one doesn’t hear the words but feels the emotions. Tchaikovsky is also one of my big favorites.

Not Bach?

Oh no, Bach is too heavy.

Whereas Tchaikovsky?

If you listen for example to his symphony number 5, the sound of the strings cut you into pieces.

How?

It feels as if you were slicing clay or cheese with a very fine and blunt string. The music transmits and cuts invisible surfaces that allow you to see the other side.

Which other side?

The side of emotions.

Ikroti, 2016 © Nicholas Hlobo/Lehmann-Maupin

Ikroti, 2016 © Nicholas Hlobo/Lehmann-Maupin

Do you know what you are doing when you paint?

No, and I don’t intend to. My philosophy is to let go of any control and to let the magic of creation operate on its own. To do so, I try to reach a state that resembles to the one experienced by a child who is dreaming. It’s a state where you are protected from the oppression of this reality. You cannot command your dreams. You are aware of what’s happening and you navigate through various of it's layers. When you dream, the pace also changes. It gets super fast and as soon as you wake up, it slows down and you struggle to comprehend and to relate to the details you encountered in your dream. It’s like a pendulum. So when I paint, I aim to let the colours and my hand do their own things. My goal is to remain a mere assistant to their process. Then comes the reading phase. I sit down and I try to understand what the process hopes to tell. I search for the unrevealed and for the surprises. Art isn’t politics. It is a space that requires total honesty. Things hide from you and one needs great concentration to allow them to be.

How does one read a canvas?

Again, by letting go of control. One doesn’t necessarily need to hear or see. One can also feel. Sometimes, this process occurs in a snap and sometimes it takes a long time. I don’t always agree with what I see or feel. Once the unrevealed appears, I enter the second phase of the process. One in which I try to attend to the lines I see. In order words, I create through layers of contemplation and action.

How much time do you need to create an art-piece?

I don’t believe in time. This said, time pressure helps me move forward. To work, I need a purpose. I guess my sense of time is similar to the one animals experience whether they are in zoos or in the wilderness. In the wilderness, animals reproduce more rapidly than in captivity. They have an urge to run, to live and the whole system around them is awake. Whereas in a zoo, they don’t have predators, so they aren’t pressured. They lose their agency. I call this state ‘vacation.’ This means no pressure and, in a way, no purpose. When I create, I lose contact with our conventional time. It’s only when I get out of my space to meet the outside world that I get back in touch with it.

In his studo, Lorentzville, Johannesburg, 2022

In his studo, Lorentzville, Johannesburg, 2022

Do you have working routines or necessities?

Cigarettes and tea. I drink a lot of tea and I only have one meal a day, in the evening. If I’m hungry in between, I have a few nuts. I’m also a late riser. I sleep in and only get fully active at dusk. When the sun sets, I rise.

Why dusk and not dawn?

The day is too noisy. My father actually used to tell me that if I didn’t manage to wake up early, I’d get fired from my jobs on the very first day. And it’s true that since a very young age, I often got in trouble for being late.

What else can you tell us about your father?

My father worked for the government. He was poor and he always told me that if I became an artist, I wouldn’t survive. He’d tell me “My son, this world is too hard. If you do art, you are going to suffer dearly.” He didn’t want me to suffer. It took him time to understand what I was doing. I got his recognition when I managed to sustain myself. And today yes, I think he is finally proud of me.

Who helped you gain recognition as an artist?

My courage. If you don’t have courage, people don’t help you. Then of course there were moments and opportunities that helped me. I always remained faithful to my work. When I was asked to work for galleries for example, I made it clear that I wasn’t working for them but with them.

If you could reincarnate, where, when, and in what would you choose to come back?

I wouldn’t come back here.

Where would you go?

As far as possible to the edge. Outside of the Milky Way. I’d love to catch up with the pace and to discover new territories.

Goodmann Gallery, Johannesburg, 2022

Goodmann Gallery, Johannesburg, 2022

If you had to choose something that is related to our planet?

If I ought to come back here, I would certainly not come back as an animal or anything that operates as a human being. Just as with humans, animals are full of greed. I often wish we didn’t have stomachs. We would be freer. I also hate the fact that hungry people are pushed to do very embarrassing things. If I’d come back, I'd rather be part of the air. Or simply to come back as something that is pure energy and that is beyond our material world. An energy that operates as a catalyst and that cannot be perceived until it’s there and received. It’s an energy which enables to form material structures and allows things to be. I actually can’t respond to your question as my dearest wish is to be as far away as possible from Earth.

But if it had to choose a body or substance that exists on our Earth?

Then I’d choose water. As everything we know needs water. Water is the closest thing to a body that I could imagine being.

What is water to you?

Something I need to respect. It can allow you to be buoyant, but it can also sink you. You can penetrate it but once you go down its heavy. You can learn to navigate through water, it exists in various forms, we breathe it, we are constantly in it but it remains a body you cannot hold without a vessel.

If you were a philanthropic billionaire, into which cause would you throw your money?

That’s ugly.

But you must respond.

It would be a non-human cause. Or perhaps sustainable energy. I would build solar fields or anything that could prevent us from harming the earth and relieve it from its troubles. For the mother is tired.

***