Born in 1972 in Moscow, Nikolaï Lvovich Lugansky is a pianist, Professor at the Moscow Conservatory and among other talents, a remarkable chess player. We met on a Sunday morning at the Montreux Palace, a hotel situated on the shoreline of Lake Geneva and known to have hosted legendary artists such as Richard Strauss and Vladimir Nabokov. Besides a few tourists in shorts, screaming children drowning in plastic and glued to their screens, the décor kept it’s belle-époque charm and atmosphere: chandeliers, gold and tapestry all over. “In which language would you like to conduct the interview?” inquires Nikoläi Lugansky who is now seated in the breakfast room. “French, English, Russian, German?” Ten minutes earlier, the hotel reception had woken him up informing him that some journalist was waiting for him in the lobby. Before turning on my recorder, he wanted to briefly test my knowledge. “ What do you know about me? ” he asked. He then informed me about his opinion on journalism. “All fake” he said. “We lost access to information. It doesn’t even make sense to call it a lie because one can say whatever he wants. What happens no longer matters. Reason for which I tend to remain skeptical when I read the media.” I tried to convince him that in our case, it would be different. I told him his words would be cautiously transcribed and submitted for approval prior to publication. His look suggested that I was missing the point, which I was. “I sometimes recognize myself when I play the piano” he said “but rarely as a talking person.” While speaking with him, I realized he had little idea which day we were and where he would be spending his following nights. “I sometimes play five to six times a week,” he said, “each time in different halls and cities.” Fifteen minutes after our interview, Nikolaï Lugansky took a seat in a black car which was waiting for him in front of the hotel. He was driven down to Italy, where he gave a concert the same evening with a different program than the one he had played the previous night in Montreux.

***

Do you have routines before going on stage? Push-ups, coffee, things you automatically do before giving a concert?

No. But that’s only because I’m too busy with the practical side of the preparation and, more importantly, dependent. Dependent on the piano, the hall, the tuner. Every tuner is different, and one needs to constantly adapt to the acoustic of the hall. The piano keys also vary from instrument to instrument. So what really matters to me is the time I have to warm up in the hall prior to the concert. If the hall is free, I like to practice two to three hours in the morning. And before the concert, I need at least half an hour to warm up my fingers.

Do you travel with special objects?

I travel with an e-book, which I systematically leave on the plane. I again forgot it this time, so I’ll need to buy a new one at the airport. Otherwise, I travel with my C.D player which can sometimes make people laugh. Especially at the US security checkpoint.

You don’t use your iPhone or iPad to listen to music?

What’s an iPad?

MP3?

I think I know what this is.

A musician which played with you in the past told me you were the opposite of a virtuoso. He told me “ Nikolaï Lugansky isn’t a showman. He is a real artist. A serious one.” Do you agree with his observation?

Probably yes. Though it’s a very stupid observation.

Isn’t there a difference between a virtuoso and an artist?

To be honest, if you are on stage you have to be a virtuoso. To remain on top of your technical possibilities you are obliged to take risks. I’d say it differently. There are some artists for whom it's crucial to immediately entertain and communicate with the audience. Then you have artists who first communicate through music and it’s through the music that they end up communicating with the audience.

So instead of feeding the audience with fast sugar in order to trigger an immediate response as virtuosos might do, real artists choose different channels?

It’s not that simple. There are some communicators, fantastic communicators, who are also great artists. Rostropovich was such.

He had both?

If you are a good artist, you need to have both. One could eventually distinguish a great entertainer and communicator from a musician. Let’s take Pletnev for example. He is the opposite of an entertainer. He absolutely doesn't care how he communicates with the public. What matters to him is the music. He even says it. “Please come to the music, if you don’t want to come, I don't care”. Then of course every piece is different. Some require immediate contact, others less.

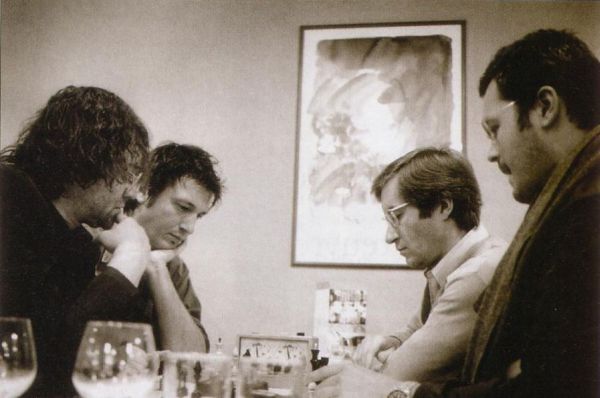

(From left to right) Alexander Kniazev, Boris Berezovky, Nikolaï Lugansky and Vadim Repin playing chess

(From left to right) Alexander Kniazev, Boris Berezovky, Nikolaï Lugansky and Vadim Repin playing chess

Last night you played Rachmaninoff No. 3, which is known to be one the most technically challenging and difficult piano concertos in the repertoire and therefore particularly suited for a virtuoso?

Yes, it is a difficult piano concerto, which requires technical capacities. But it’s far from only being a virtuoso piece. It’s also very intellectual and unbelievably emotional music. And indeed, some phrases require to immediately touch the audience. But you see what we are doing now?

No.

We are creating concepts. Distinctions which simply don’t exist in music, because music manages better than words. In music like in life, these differences are way deeper than what we are now trying to produce with our thoughts.

Montreux, Switzerland, 2019

Montreux, Switzerland, 2019So let’s go back to subjects which might be better suited to language approximations. Did you ever experience periods in your life which were dark. I’m thinking for instance of Vladimir Horowitz who suffered from a twelve-year depression. Why are you laughing?

Because! Indeed, there is period in Horowitz’ life, where he didn’t play in public. But I’m pretty sure it wasn’t due to depression.

Introspection?

He studied. He did some important recordings, he did many things. If I’m laughing, it’s because when we talk we often project our own feelings on others. Which I’m now also doing with Horowitz. Yet, I don’t think that the introverted world of Horowitz was as fragile as you think. Sure, all artists are different. But in order to perform like Horowitz did for so many years you must somehow be quite simple.

Simple. Why?

Otherwise he would never have managed to play until 85. It's so much stress to perform. You must understand that every performance is a kind of failure.

Because you never manage to succeed?

You never arrive where you planned to arrive in your head.

Ever?

Sometimes you get closer, sometimes further, but you never get there. My point is that playing piano on stage destroys you. And the fact that Horowitz played concerts till his mid 80s meant his nerves were fine.

Are you implying that each time you play on stage, you are giving away or losing a part of yourself?

Yes. Each time, you realize that what you wanted to do during months and years of studying is nothing. It’s just like agriculture. You do, you do, and then it rains, or it hails, and all your work is destroyed.

Can you predict before going stage whether you're going to be closer or further to your idea of perfection?

Occasionally I think I know but of course it's never true. Sometimes I’m just better prepared, but I’m incapable of guessing how good or how bad I will play during a concert. It always just depends on the second.

You generally play on a Steinway?

Yes, but I can also play on other pianos.

Doesn’t Mikhail Pletnev with whom you were playing last night ( though he was conducting) travel with his own piano?

Sometimes yes. It’s actually Vladimir Horowitz who was the first to initiate this system. When he was in his seventies, he started importing his own piano. One which had been specifically constructed for him. This can for sure be helpful.

Moscow, 1986

Moscow, 1986

You were a child prodigy. How did this happen?

When I was five, my father discovered I had perfect pitch and he was pretty impressed by it. So he brought me to a music school in which this faculty didn’t astonish anyone. Yet, he didn’t let go as easily. Do you know what’s a dacha?

Yes.

It’s a country side house but not like in Verbier or in Gstadd. The purpose of a dacha, at least at the time, was to cultivate vegetables and fruits. It was a place where people worked sometimes extremely hard. It’s thanks to dachas that many families survived during the perestroika. Anyhow, next to our dacha was a man called Sergei Alexandrovich Ipatov. A professional pianist who had been brought up in an orphanage and who experienced a difficult destiny. But he remained a very talented musician. He was also the only person in the village to own an upright piano. So my father introduced me to him shortly before I turned 6. At first, he remained quite distant. When I started playing a Beethoven piece by memory, I remember seeing him opening up. After this encounter he agreed to give me lessons. That’s how I managed to enter the Moscow Central Music school a year and half later.

Could you briefly describe your family background?

My parents are typical Soviet Union citizens, who both strongly benefited from the Soviet educational system. My mother was born in 1942 in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. Her family had been relocated from Krasnodar to the south east after the Second World War evacuation. At 16, she left for Moscow to study. As for my father, he comes from a village near Kaluga situated 200 km southwest from Moscow. His father - my grand-father - spent 8 years of his life imprisoned. First in Germany, where he was held captive in a Nazi working camp, then in USSR, where he was accused of having collaborated with the Nazis. Most war prisoners who came back to Russia in 1945 were imprisoned again for not having fought against the Germans. My grand-father, who was innocent, had to wait for Gorbachev to come to power to be officially acquitted. He was a very impressive man who died not that long ago, at the age of 89. Anyway, to come back to his son, my father, he went to school in Kaluga. Then, when he was about 17, he left for Moscow. He had been accepted to study physics in the Technical Institute, which was quite prestigious considering his provincial background. And that’s where he met my mother. He was already working as a physicist and she as a biochemist. When they started dating, my mother invited him to the Bolshoi theater to see La Traviata. My parents for sure appreciated music, but never did they expect or plan to have a musician in the family! I also have an older brother who lives in Moscow, but he is slightly more hippie than I. So I come from a quite normal family, in which nobody was a musician and it seems likely that my children, nieces and nephews won’t be either.

How and when did you start performing in public?

The Soviet educational system was unique. First of all, you could only study music if you were very talented. Then there were all kinds of auditions. If you played decently you would be asked to perform concerts in halls or galas evenings throughout the Soviet Union. When I was 8, I played my first public concert. I performed Mozart Fantasy D minor in a small hall of the Moscow Conservatory. Since then I never stopped playing in public.

Did you try other instruments?

I might have tried the violin for a week or so.

New York, 2015, © Tina Fineberg for The New York Times

New York, 2015, © Tina Fineberg for The New York Times

As a child prodigy, did you only experience success?

As a child I had some success yes, but I was far from being as famous as some of my peers. Eygeny Kissin, Vadim Repin, and Maxime Vengerof for example, were extremely famous from age nine, ten on. I wasn’t. There were also many very famous kids my age who later became nothing.

If you could be reincarnated and choose the era, the country, the profession, anything, what would you choose?

Alain Delon ( laughing)

Really?

Why not?

Let’s say you are a philanthropic billionaire and you are obliged to give away some of your money, to which cause would you give?

What immediately comes to my mind - it's not very interesting - but there are so many unhappy ill people out there. I’m thinking specifically of old people. If a child is ill it’s a tragedy for everyone. Of course. But to get money for children is easier than if you are old. When you are alone and 75 years old and sick, no one cares. And we in Russia can for sure not be proud of our elderly homes.

***