Matthias Weischer is a painter. An artist too, of course, but in the traditional sense of the term. He masters technique and doesn’t employ an army to realize his art. He can draw and paint anything; explore every style. He works alone and is in absolute control of his artistry, which continues to evolve over the years. His work is often linked to the New Leipzig School movement, which emerged at the end of the 1990s.

I met him on a freezing afternoon in February 2019 at his studio in Leipzig, hidden in the trendy Baumwoll Spinnerie, an old cotton quarter warehouse now renovated with working studios for artists. He kindly served me a cup of black coffee, responded to my questions and gave me a tour of his studio and canvases in progress. Impeccably organised and filled with indirect light, his atelier imbues the same atmosphere found in his paintings. Sharp colours and objects assembled in a theater-like fashion strewn left and right.

Throughout our discussion, I visualised Matthias Weischer as a bottle being thrown into the sea. One which contains and is animated by a poetic quest, yet immune to strategic missions and artistic trends. Power relations don’t seem to affect him. Nor does he seem to force his destiny. All he seeks is a quiet space in which he can work, undisturbed.

The way in which he narrated his life to me seemed to be shaped by the forces of coincidence. Matthias Weischer started painting through his own initiative, arriving in Leipzig par hasard. He had barely finished his art degree when he was propelled at the height of the 2001 art bubble. Nothing in his personal trajectory as an artist has been planned or foreseen.

***

Can you tell me more about Elte and your childhood ?

I’m afraid there isn’t much to say on Elte. There are maybe 1500 people living there, most of them working in agriculture. In the seventies, it became part of the Rheine. That’s about all you need to know about Elte. My father was the director of a school for mentally disabled children and my mother was a housewife. I have four brothers and I’m the youngest of the family.

The youngest and the only artist of the family?

Yes. I might have been less controlled by my parents than my older brothers. No one ever asked me what I was doing and maybe, for this reason, I started painting.

How old were you when you started painting?

Fourteen or fifteen. I found some colours in the house and installed myself in a little corner in the attic under the roof. I’d go up there and draw. I started with self-portraits, as I didn’t have any models. All I needed was a mirror, colors and paper. But I never took any lessons while living in Elte, nor did anyone really pay attention to my drawings.

But you were quite good at it?

I don’t know. I think I was ok. Good enough to continue. I saw it as promising or at least worth going on with.

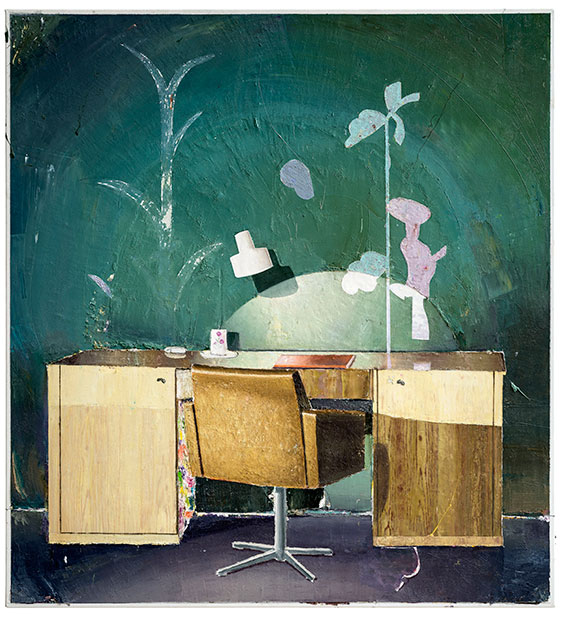

Desk, 2019

Desk, 2019

Was becoming an artist a childhood or adolescent dream?

No, I don’t think my aspiration towards art was connected to any romantic dream of this kind. I never had any vision of becoming an artist or existing in the role of an artist. But painting became a necessity. I was naturally driven towards it, almost without consideration or thought.

Because you liked it?

Yes, and I might also have seen it as a chance to free myself from the situation of the village and to get out of there. Many of my childhood friends made their lives in Elte and happily so. But my intention was always to leave.

Getting out the village was your plan. Were there any other experiences linked to this desire to escape?

Not really no. I wasn’t looking for a decision. I just knew I wanted to get out of there and then see. I felt painting was doing something to me. Maybe it helped me, I don’t know. I always felt better when painting. It was and still is an activity which challenges me. I want to constantly get better at it. It’s not a competition with others, but one I have with myself, I’m not sure I can explain this more.

Your parents weren’t pushing you in a certain frame of career?

No, they let me quite free. I finished school, worked for 15 months in a retirement home for my Zivildienstand then slowly made my way to Leipzig.

Why Leipzig?

My older brother was living and working there. He told me it was a great town and encouraged me to join him. When I arrived, I felt this energy that interesting things were happening. In 1994 Leipzig was quite different from today. It was a very exciting place to be.

Was Spinnerie already an artistic hub in 1994?

There were a few artist studios but mostly empty spaces. I started looking for my studio, here in the Spinnerei in 1995.

And then you got stuck.

Exactly. Stuck. I even live here now.

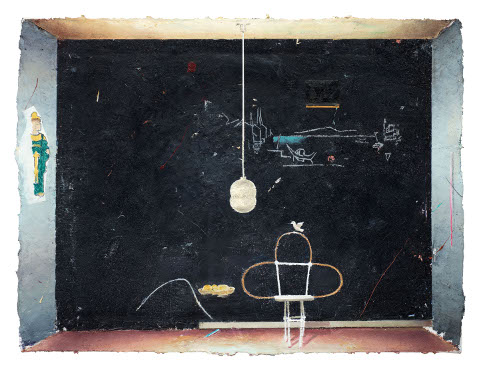

Schwarze Wand, 2013

Schwarze Wand, 2013

So you didn’t come to Leipzig specifically to study the rigorous painting techniques of the East?

I was quite naive back in the day. I was thinking about applying to an art school in Munster. Then I arrived in Leipzig and discovered that I could also study painting here. That’s how I ended up at (HGB) the Academy of Fine Arts Leipzig. I started in 1995, got my first diploma in 2000 and then studied for another three years.

You hadn’t even finished your studies when your paintings were trading at auctions for half a million dollars. How did this happen?

I don’t know what happened there. I think an important factor came from the intensity of work that myself and others accomplished while studying at the Leipzig Academy. We were a group of painting students, all very ambitious and working from morning to night. We would communicate a lot amongst eachother. The teachers were ok, but I don’t think they influenced us that much. The stimulation really came from within the group. At the time, painting wasn’t popular. The opposite in fact. The trend was to declare painting dead. There were also tensions arising inside the Academy. The painting department was at stake. People were fighting to get rid of it entirely. I think, in part, this hostility towards our art and practice challenged us painters. It stimulated the painting students to fight for what we were doing, what we were studying. And we did fight, the department was not closed and we graduated with diplomas. Then suddenly, we found ourselves asking what to do next. Some galleries were interested in us and at some point, ten of us opened a gallery together in Berlin called LIGA.

Did Neo Rauch have a role in the sudden explosion of the New Leipzig school movement?

Neo Rauch wasn’t part of our group. He is older than us. When I was a student, he was an assistant professor professor, coming from time to time to the studio to discuss with us. But he wasn’t a key figure in our studies. Yet, it’s thanks to him that people started coming to Leipzig and showing interest in what we were doing. Neo Rauch opened the door to the attention that myself and others then received. Gallerist Judy Lybke also played an essential role in my career. He kept a focus on some of us and would send collectors to Leipzig see our stuff. Through his gallery Eigen + Art, I had the opportunity to exhibitin Berlin. Collectors would come and see that what we were doing was good quality for cheap and they started buying like crazy.This enthusiasm turned into I suppose a kind of boom or something.

Is there something to be said on the period which followed this boom?

There isn’t much to say really. At least in terms of my work, nothing changes. I continue doing exactly what I have always been doing: painting.

in his studio, February 2019

in his studio, February 2019

Do you have routines that you need to follow in order to be productive?

Since three years or so, I’ve been getting up between 6am and 7am and start working by 7h30, latest 8. I work until noon, have a break and spend the rest of my afternoon working.

So you are quite regular. Almost like in an office. You take a proper lunch break?

Well I have to eat something.

But you are not procrastinating for 3 days and then working non-stop for 3 nights and days in a row?

No, this I never do. I’m quite structured. I have always been working a lot, but on a daily basis.

Do you have weekends?

Normally not. I work every day and from time to time, I take half a-day off.

Do you have special needs? A certain amount of coffee drinking, hours of sleep you absolutely need to focus?

Not really no. I need it to be quiet. And I like listening to music while I paint.

So you can work basically everywhere?

Yes. I have no special needs or rituals.It’s always been easy for me to dive into work. I just look at the work and I know what I have to do. It’s as if the canvases are demanding something from me. I quickly get into the process.

When you start a painting, do you know where you are going?

I know more or less where I’m going. Nevertheless it’s always surprising. I start with a rough idea, but then this idea matures and grows in its own direction. I work on several paintings at the same time...all overh long periods of time. And I never know where they will end up. They are all growing up together like a group or like a family. They hang on the walls of my studio and I go from one to the other.

How many canvases are you working on right now?

Fifteen. And every morning when I arrive in my studio there's something to be done. I never experienced a situation in which I didn’t know what to do.

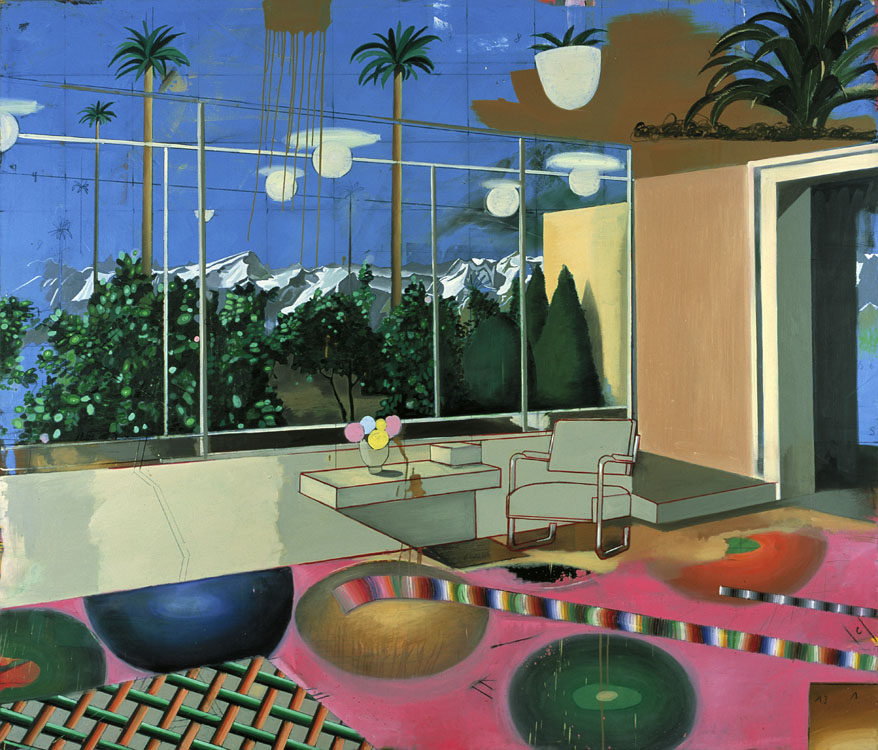

Terasse, 2001

Terasse, 2001

You never arrive in your studio telling yourself that you must start all over again or that nothing makes sense?

No, this never happened. But I also have different activities. If I don’t know what to paint I draw and if I don’t know what to draw…(laughter) I paint. And, I’m also doing sports, I go running regularly. This is actually a necessity for me. To get out of the studio. It’s not that I’m working non-stop and never going out either!

Do you have any other passions, hobbies, like tennis for example?

Tennis! I started a few years ago and I love it.

Any other passions?

No, I honestly don’t think there's not much space left for me to develop new passions.

Is there an artist which influences or inspires you a lot?

David Hockney had and still has a big influence on me. He brought me back to landscape paintings. I had the chance to work with him and in my opinion, he is one of the best living painters in the world. He is a universal mind and master. One which influenced me to a point where it almost became difficult for me to find my own voice again. Eventually, I got back to it. Yet, Hockney remains a constant source of inspiration for me.

Matthias Weischer attends the hanging of David Hockney's exhibition Hand Eye Heart - Watercolours of the East Yorkshire Landscape. Los Angeles, U.S., 2005.

Matthias Weischer attends the hanging of David Hockney's exhibition Hand Eye Heart - Watercolours of the East Yorkshire Landscape. Los Angeles, U.S., 2005.

Any dead artist that inspire you?

There is Vermeer, Vuillar, Fra Angelico, Picasso, Sasseta, Kitaj, many actually.

If you could reincarnate, choose the era, the country, the profession, the gender – who would you be?

A cave-painter 40000 years ago in the south of France. I imagine it would have been deeply fascinating to witness the beginning of art and to understand what this meant for the development of mankind. I visited a couple of years ago the Cave of Chauvet, a replica of course, and I asked myself, how did they manage to become such good draftsmen, how was their training and in which form did they communicate about the images. To be able to know, what really happened during this time, would be a strong motive to reincarnate. Otherwise the idea to reincarnate and live a whole life again is not very tempting, maybe two weeks would be enough.

Let’s say you are a philanthropic billionaire and you are obliged to give away some of your money. What cause would you support?

Spontaneously I would go towards environmental issues. Which is maybe even something I’m aiming to do through my landscape paintings. Trying to offer a certain point of view on nature and honor it. I’d love to save nature or at least give people a different consciousness about it. Not sure you can buy this with money though. But persevering and honoring nature is what I’m actually thinking of while painting landscapes.

Do you like windmills?

They are very aggressive to the landscape and therefore hard to integrate in a painting. Windmills destroy our landscape for sure. Now if you look at Dutch paintings from the past, you have windmills and they aren’t a problem. Yet, I've never seen a contemporary artwork or painting in which modern windmills were successfully integrated. I think we should find images to do so.

If artists manage to reveal to us the beauty of windmills destroying the harmony of a landscape...

This would of course be very helpful. It would be a great achievement if an artistmanaged to make something nice around these windmills.

Windmills are particularly prominent around Leipzig,

Bavarians wouldn’t allow such constructions on their land. So they say, “bring them to Saxony Anhalt”, and here they are.

Quite a landscape you have here around Leipzig. Nice and flat forever.

(Laughter. )No of course it’s really hard to be here as a landscape painter.

Let say it’s not an obvious choice.

I suffered from it believe me!

***