When political theorist, feminist and decolonial activist Françoise Vergès told me that if she could reincarnate, she would come back as a tiger, I was confused. From an author whose life and work is dedicated to protecting the weak from the strong and denouncing patriarchal and neoliberal oppression, I was expecting another answer. A daisy or a butterfly, anything less predatorial would have suited. Yet she insisted on the tiger. “The way it moves, the beauty, the speed, the sensation of freedom it conveys are all features I wouldn’t mind experiencing one day.” Having classified Françoise Vergès in the radical-left feminist department, one that is all about male castration and virile extermination, no more straight lines, only curves, I objected, “ Tigers are predators. Killers!” Seeing what I was getting at, she laughed. “Of course, tigers are predators. They kill to eat, but you can’t compare a tiger with a white man who goes to America to kill 300,000 buffalos just for fun.”

Born in Paris in 1952, Françoise Vergès was brought up in La Réunion, a colonized island situated south east of Africa. She finished high school in Algeria and worked for eight years as a journalist and editor for various feminist publications. In the Early 80’s, she left for the United States where she lived illegally for two years, ‘’cleaning, cooking and doing secretarial work for rich people.” She then decided to sort a few things out. “I went to Mexico, applied for a US visa, enrolled at the University of San-Diego, obtained a double bachelor’s and moved to Berkley where I completed my PhD.” A former professor at Berkeley University described Françoise Verges as an authentic militant. “Anticolonialism is not something she learned in books,” he said, “It’s rooted in her entire being.”

Author of a dozen essays on race, colonialism, slavery and feminism, Françoise Vergès is currently a public educator, independent curator, feminist activist and writer. Her last book “ Une théorie feministe de la violence: pour une politique antiraciste de la protection” published in France at the end of 2020, sheds light on state-supported institutions such as the justice system and prisons, which paradoxically, by aiming to decrease violence, contribute to enhancing it.

Vergès’ mission isn’t to condemn violence unanimously. Her focus is rather drawn to unrecognized, invisible forms of violence that annihilate chances of living with dignity from as early as the womb. Without aiming to offend Germanists, Rilke’s Der Panther offers, I believe, a perfect image of the type of brutal and blind violence Vergès is denouncing. A marvelous black feline crushed behind bars, humiliated and reduced to a passive piece of flesh, yet kept alive to amuse the gallery.

The following interview was conducted through screens in December 2020, while Francoise Vergès was in her home in Paris, I in Geneva.

***

Where does your activism come from?

I grew up with two activist parents who never hid anything from us. When things got tough, for instance when the police would burst in to search our home, they didn’t take us out or try to protect us by diminishing the threat and the importance of the events. They would rather explain what was happening to us and why. This early exposition to the legitimized violence stimulated my curiosity; my desire to understand what lies behind actions that intend to instill fear or, on the other hand, to create a sense of protection, love and solidarity.

Does your style, crisp and factual stem from an emotion of anger?

My writing and actions rarely come from abstract questions or theories. They are embodied in experiences I have dealt with that infuriated me. More than anger, I would say that I’ve always been particularly sensitive to humiliation. The way, for instance, patriarchy, racism and capitalism gain power through daily rituals of shaming. I remember how teachers would humiliate black girls, calling them stupid or ugly. This drove me crazy. I was lucky to have supportive parents. When I would challenge authority, talking back to teachers for example, my parents would never punish me. And to this day, I still feel deeply connected and inspired by those who find the courage to stand out there. Even though they are told that nothing can be done, they are not afraid to challenge the violence of normalization. They know things can be otherwise and they act.

Françoise Vergès with her mother, Laurence Deroin-Vergès

Françoise Vergès with her mother, Laurence Deroin-Vergès

The submission and the exploitation of the other isn’t natural you say, but constitutive of our racist, neoliberal and capitalist economy. How so?

Don’t get me wrong. I’m far from having a romantic idea of a society where everything was nice and harmonious until capitalism and racism arrived and destroyed it all. Absolutely not. I do, however, believe that capitalism and racism, which developed hand in hand with colonization and the slave trade, have immensely exacerbated violence. ‘’Capitalism is the fabrication of a differentiated vulnerability to premature death,’’ says Ruth Wilson-Gilmore. This means that some people are “condemned” to die prematurely, and this will be justified. The division between the fully human on one side, and the less human on the other, began with the slave trade and has never ceased since. Today, a great part of humanity is dying prematurely due to pollution and exploitation. People work in conditions that exhaust their bodies and their health, and because they are trying to survive, they are forced to accept such conditions imposed on them by exploitative capitalism. This distinction, between lives that matter and lives that matter less, were again made evident during the pandemic. The wealthy were protected over precarious and racialized populations. The life expectancy of slaves on plantations was of eight to ten years. Their lives did not matter, they could be replaced.

Hasn’t the distinction between lives that matter less or more than others, thus the justification of exploitation and slavery, always existed through history? In Bhutan or China to take a nonwestern example, slavery is still common today.

Slavery existed way before colonialism, but none of these systems were able to impose themselves on the global scale. This doesn’t make them acceptable, but nonetheless different. The slavery that emerged in Europe from the 15th to the 19th century and which led to the deportation of millions of Africans, transformed the world economy. Maritime commerce became international: new laws, banking systems, insurances and trades were all able to expand precisely because they were rooted in and sustained by anti-blackness. Anti-blackness enabled the development of new social and cultural norms that justified the importation of goods like tobacco, chocolate, sugar and so on. Today, these structures have still not been fully questioned or dismantled.

You question one of these structures in Une théorie féministe de la violence by analyzing carceral feminism. Could you tell us more?

Carceral feminism aims to confront violence against women by advocating prison and punishment for men. The idea is that this type of crime deserves heavy punishment. Yet, as we know, sending men to prison has never prevented violence against women. On the contrary. Prisons are institutions that promote violence, and where men are either victims of violence through isolation, rape and so on, or must resort to violence themselves to survive. The other problem of carceral feminism is that it’s a class and raced based solution. It only protects, though never entirely, some women, ordinarily the ones belonging to the bourgeoisie. The others are either experience rape, murder or criminal convictions with very few avenues of recourse. As for the incarcerated men, they are usually racialized men. Therefore, by delegating the power of protection to institutions such as the police and the state judiciary system that are themselves racist and sexist, carceral feminism contributed in the exacerbation of violence.

Are you against prisons?

I’m in favor of a restorative and reparative justice. The latter has been experienced in some parts of Africa, North and South America, and the results were promising. Restorative and reparative justice means working with the perpetuators, going for instance to youth detention centers to try to understand how crime has become, for some, the only possibility to survive. The objective is no longer to punish violence through violence but to understand it. We live in a society that feeds violence. People are increasingly stressed, exhausted, anxious, they feel trapped and powerless. Some end up turning against the more fragile to release themselves. I’m not saying there is an easy solution for preventing violence against women, but I believe that with some imagination, we can leap into new possibilities and ways of repairing instead of punishing. What most women seek when they go to the tribunal is for the crime to be acknowledged. The sanction that follows doesn’t necessarily make them happy. For these women, reparation doesn’t occur through punishment but first through recognition.

London

London

In your last book, you refer to women, including Ivanka Trump, who claim to be feminists and who support philanthropic feminist-oriented deeds which paradoxically, you say, contribute to the perpetuation of sexism, racism and inequality.

I indeed discuss the infamous white savior syndrome – the need to save the “other,” usually a non-white person. This position tends to assume that these “other” women are passive victims, whereas most of them strive to survive, fighting every day to take care of their families and their children. Saving them, for example in Ivanka Trump’s Women's Global Development and Prosperity Initiative, means integrating them into an entrepreneurial neo-liberal ideology and self as a capital to exploit. The aim isn’t to invest in a reparation policy that would facilitate women's autonomy, but a proposal to become debtors of the banking system. There is, in my opinion, something obscene about going to Africa with one’s millions and then congratulating oneself for it. A reflection should proceed such actions. Why, how and from where did I get these millions? Why are philanthropic deeds the only way to change the world? I’m not saying that these millions don’t help people, but simply that they don’t challenge the origin of the problem. Studies show that when the Gates foundation finances a project in a disadvantaged country, they generally also seek control. We know that the microcredit fashion in India indebted women far more. Of course, there are examples of women who, thanks to microcredit and access to capital, managed to send their children to school or to open a business. Yet, these rare successes don’t question why can’t these women send their children to school in the first place?”

If you have money what are you supposed to do, give it to the State?

Not necessarily, because most of them are corrupt and have given up general interest and public services. Yet the fact that a western private foundation can enter a country and take control is something that deserves to be questioned. Corporate philanthropy, whose money, as we know, comes from exploitation and privatization, merely depends on one person’s generosity. Solidarity on the other hand, stimulates community thinking and solutions. For example, you have communities in Africa that try to create their own access to medical goods by building their own research and production, in order to become independent. Generally, as soon as their efforts start to show, an international law will emerge and the big pharmaceutical companies will then take over. There is no easy solution. One can’t just snap one’s fingers and expect change to occur. The path is long, requires, a global awareness and, I believe, at the root of it all, a radical change in the commodification of everything.

Therefore, the end of our capitalism and neoliberal economy?

For sure. Because as long as capitalism perpetuates, we will have no other choice than to continue to live in a world that is being destroyed. Capitalism means oppression, extraction, exhaustion of energy (human, fossil, subsoil, soil, plants, animals), racism and exploitation.

Are you suggesting a return to communism?

If so, in a very different form from that, which we have experienced, for example, in China and the Soviet Union. These systems were based on productivism and extractivism and didn’t respect the environment in the slightest. I don’t know where the solution lies, and I have none. I do think, however, that we can learn by questioning, looking elsewhere, studying different ways of inhabiting the world, for instance the example of indigenous people. We can also rethink and invent new forms of social organization, ways of building families which are not limited to the mother- father-children structure and so on.

Red Square, Moscow 1968

Red Square, Moscow 1968

Yet, being born and raised in a capitalist system, I don’t see how the world could function better differently. The measure of productivity through money seems to be the only path that provides us with, at least, an illusion of freedom.

Our lives are so saturated with commodities that it is difficult to see and imagine anything else. Yet, we know that this system, which is based on productivism and extraction, is destroying the planet on which we live. And there is no other planet. According to the UN and the WHO, one of the main causes of premature death in the world is pollution. The world has been deeply damaged, not just on the human scale, but everywhere. The forests, the earth, the oceans. So we have no other choice but to think of ways to repair our world. It’s a collective responsibility that can, for instance, begin by challenging the racial capitalist and imperialist violence inflicted on humanity and nature. By imagining and finding ways to live differently, we can avoid the expansion of inequality. There is no way we can continue to justify the comfort of a few at the expense of the total exploitation of others. The fact that children come into the world every day with no hope or possibility of ever going to school and are, or will be, deprived of a healthy psychological upbringing, is simply unconscionable.

But hasn’t the world always been an awful and unjust place, ravaged by famines, wars and epidemics?

Yes, but most of these ailments were not generated by a neoliberal lifestyle. They were without any doubt destructive and caused utmost suffering, but they weren’t the consequence of unfettered hyper-consumption, global trade, agribusiness, exploitation, wars and militarized borders. Colonialism imposed a global system of inequality and injustice. And today, famines, result from a neoliberal and capitalistic economy, which overvalues productivity and scarifies the lives of so many.

What can be done?

Repair. Restore, work through multiple temporalities to collectively heal the past, the present and the future. Move from Man (white, rich, male) to human. The way racism infiltrated European institutions, not only in the ideologies of Nazism and fascism but in liberal ideologies, has not yet led to deep self-reflection. Racism is still seen as something from the past that only survives amongst uneducated people. An antiracism struggle that questions why prisons in the USA are predominantly full of young black men, in France full of young black and Arabs and why people of color as we say in English (even though I’m not a fan of this expression) are always among the most exploited needs to be questioned. Reparation can only occur if we start by questioning how vulnerability to exploitation is fabricated, how the exploitation of racialized people is justified and how wealth and comfort in the global North are seen as “normal.”

With philosopher Nadia Yala Kisukidi during Paris demonstration, 2019

With philosopher Nadia Yala Kisukidi during Paris demonstration, 2019

Let’s say I’m a white bourgeois feminist mother who illegally employs a Filipino cleaning-lady/baby-sitter to take care of the household and my children whilst I’m out there empowering myself by writing articles or by launching a sustainable online clothing brand. If I don’t give this woman a job, she might end up on the streets. Therefore, am I not doing good by hiring her?

Wanting to “do good” is, in my opinion, problematic, but let us leave this subject aside. In the situation you describe, I think what is crucial is that this bourgeois woman become conscious that her privileges rest on the exploitation of others. Her free time, the space in which she lives, the possibility she has to pursue her goals, are not only the result of her exceptional talents and competences but mostly enabled by the woman she exploits; a woman who probably did not have any other choice than to leave her country to come work twelve hours a day in a country where she has no papers. How come this woman had no other choice? Is it normal? What is important to understand here is that this isn’t normal. Slavery was normalized. Likewise today, the fact that some privileged lives rest on the oppression of others. And this isn’t normal or natural.

What could this bourgeois feminist mother do besides to be eaten alive by the guilt of her privileges?

I don’t think guilt is constructive. It can to reflection but then it should be followed by something else, an awareness. If this woman claims to be a feminist and walks around talking about justice and equality without acknowledging that her own lifestyle is made possible by women who are doing the job she should otherwise be doing, then it is problematic. Every oppressed woman in the world knows that there are two jobs she can always do to survive: sex work and cleaning. By doing one or the other she is remaining active, she is fighting to keep her dignity. We can also say, in all honesty, that if this woman had the choice, she would perhaps do something else. What is essential in the case you describe, is recognition and therefore, the end of exploitation. To understand that it is not the money that one is giving to this woman that is helping her out but rather the recognition of her decision to be exploited to survive, feed and send her own children to school. This has dignity and deserves respect. She is not a passive victim whom you are helping.

When did you start writing?

I always loved writing. In school I would write fiction. When I turned 13 or 14, I started writing activist texts while participating in different struggles in la Réunion. I later worked for a militant newspaper, became a professional journalist and the rest you know.

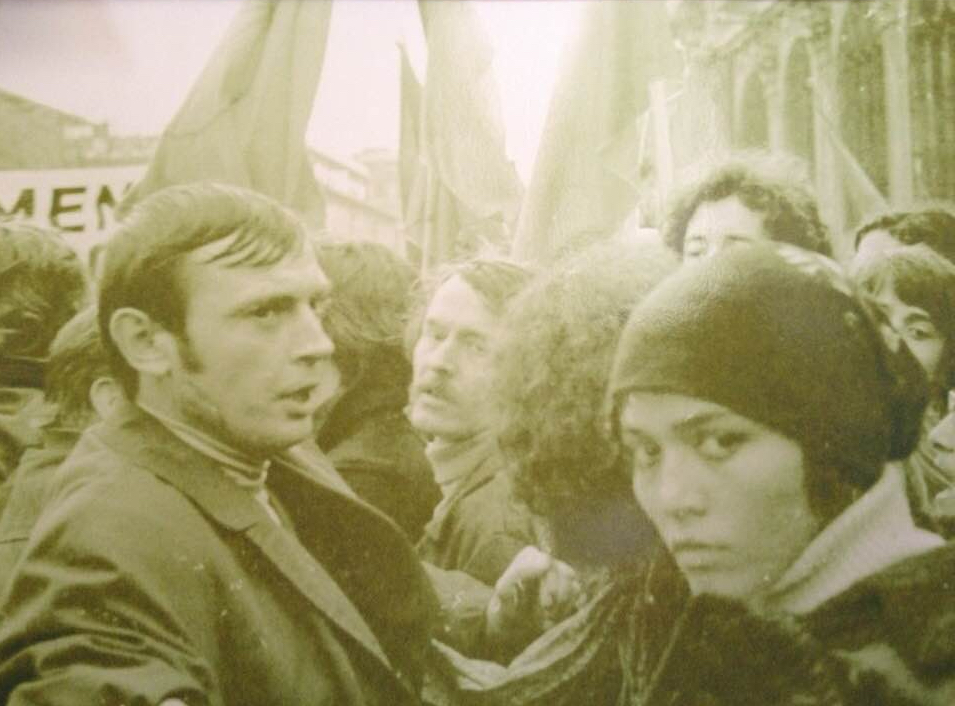

Anti-imperialist demonstration against US war in Vietnam, Paris, 1970

Anti-imperialist demonstration against US war in Vietnam, Paris, 1970

Do you have any routines?

I generally wake up very early and start my day by reading the news from all around the world, Europe, Asia, Africa, America. What interests me is to see what matters in which place and how. I then either go out for a walk, do some yoga or go to my computer and write. Cooking is also central to my routine. I cook something new every day. Otherwise, I watch many movies and read. Every week I try to read at least one novel in order to avoid being exclusively absorbed by essays. Sometimes, literature responds better than essays to the human psyche and its difficulties.

Besides reading, where do you get your inspiration from?

Through social interaction. And by being challenged and forced to reassess my views. This is not always easy, as we dislike recognizing our mistakes and limitations. Since I value my independence, I can be rather stubborn, but fortunately I am incapable of holding a grudge. I enjoy informal social interactions such as cooking and eating with others. Whenever I travel, I go to markets to discover new ingredients, new ways of cooking. I have a passion for the art of weaving and for textiles, their smell, their touch. And I’m in awe of the human capacity to create beauty. I actually used to make many of my own clothes, and I plan to do it again. Otherwise, I regularly participate in marches, demonstrations, political activism, decolonial feminist debates and actions.

If you were a philanthropic billionaire, in which cause would you invest?

I would finance a huge university campus that would be intergenerational, meaning it wouldn’t only be destined for the young. It would be a place where all sciences and humanities would be taught as well as crafts. There would also be a space dedicated to reflect on reparation and to imagine the future.

If you could reincarnate and choose the country, profession, personality, anything what would you choose?

I’d actually be curious to experience life as an animal. If I could choose, I would come back as a Tiger in India or in Siberia.

***