We met end of the summer 2020. I was in Bretagne, France; he waiting for winter to end in his house in Johannesburg.

***

You refuse to be defined as a post-colonial thinker, how come?

I have nothing against postcolonial or decolonial theory, but I am neither a postcolonial, nor a decolonial theorist. My story has been one of constant motion. I was born in Cameroun, I spent my twenties in Paris, my early and mid-thirties in New York, Philadelphia and Washington. I later moved to Dakar, Senegal and I’m now in Johannesburg, South Africa. Likewise, I was trained as an historian, then I studied political science. At the same time, I read a lot of philosophy and anthropology, immersed myself in literature, in psychoanalysis. As we speak, I am familiarizing myself with life sciences, climate and earth sciences, astrobiology. This perpetual crossing of borders is what characterizes my life and my work.

So how should one define you?

I’d rather define myself as a penseur de la traversée. One for whom critique is a form of care, healing and reparation. The idea of a common world, how to bring it into being, how to compose it, how to repair it and how to share it - this has ultimately been my main concern.

© Stephanie Fuessenich/laif für die FAZ

© Stephanie Fuessenich/laif für die FAZ

In your last book, Brutalism (Editions La Decouverte, 2020) you plead for a politics of the en-commun (in-common) as a means to re-enchant the world and re-infuse solidarity among the elements which constitute and belong to this one world we all share together. Does your concept of the en-commun have any affinities with communist ideas?

No, it has nothing to do with communism as a political ideology. It is related to my preoccupation with life futures, and as I have just said, with theories of care, healing and reparation, the reality of historical harms and debates on planetary habitability. Ultimately Eurocentrism has fostered colonialism, racism and white supremacy. Postcolonialism has been preoccupied with difference, identity and otherness. As a result of my deep interest in ancient African systems of thought, I am intrigued by the motifs of commonality and multiplicity, by the entanglement of all human and non-human forms of life and the community of substance they form. This commonality, I should add, must be constantly composed and recomposed. It must be pieced together, through endless struggles, and very often, defeats and new beginnings.

Isn’t difference the basis of identity?

During the 19th and 20th centuries, we have not stopped talking about difference and identity. About self and the Other. About who is like us and who is not. About who belongs and who doesn’t. As the seas keep rising, as the Earth keeps burning and radiation levels keep increasing and we are less and less shielded against the plasma flow from the sun and surrounded by viruses, this is a discourse we can now ill afford.

Does this imply hierarchies should be more horizontal?

By definition, all hierarchies should be exposed to contestation. I am in favor of radical equality. Formal equality is meaningless as long as certain bodies, almost always the same, remain trapped in the jaws of premature death. Once equality is secured, we need to work on the best mechanisms of representation. But those who represent us can never be taken to be hierarchically superior to us. Instead they are called upon to perform a service for the care of all. Representation can only be the result of consent and for such consent to be granted, those who represent us must be accountable. Nobody should make decisions on behalf of those who haven’t mandated him or her. The great difficulty these days and for the years to come is that decisions are increasingly made by technological devices. They are determined by algorithmic artefacts which have not been mandated, except possibly by their manufactures.

Do you have a mission?

I wouldn’t want to make things uglier than they already are. I’m here on earth like everyone else for a limited timeframe. A tiny particle in a universe governed by ungraspable forces. My goal is therefore to remain as open as possible to what is still to come. To welcome and embrace the manifold resonances of the forces of the universe. On my last day, at the dusk of my life, I want to be able to say that I have smelled the infinite flesh of the world and that I have fully breathed its breath.

Writing is your medium. How did this practice come to you?

I used to be shy. It was easier for me to write than to speak in public or even in a group. When I was 12, I was part of a poetry club at my boarding school. In parallel I kept a personal diary in which I would relate my daily experiences. But it was only when I turned 18 or 19 that I started writing, that is, speaking in public.

What does writing mean to you?

It enables me to find my own center. One could almost say “I write therefore I am.” It’s a space of inner peace, though it can also at times be one of self-division. Whatever the case, what I write is mine and can never be taken away from me.

Do you have any writing routines?

In order to write, I need silence. I need to be left alone for long hours, if not days. Silence for me is a prelude to a state of psychic condensation. When I was younger, I’d mostly write in the pitch dark, after midnight. Writing after midnight, I could reconnect with Africa’s deepest pulsations, its tragedies as well as its metamorphic potential, the promise it represents for the world. That is how I wrote On the Postcolony, in the midst of Congolese sounds and rhythms.

How do you reach this bubble of isolation and silence while living with your spouse, children and dog?

My wife is a writer of her own account. The dog is a very unobtrusive companion. It also happens that I can be talking to you now without really being present. Being physically present doesn’t prevent my mind from being totally elsewhere.

Where does your writing start?

Most of the time in my head. Sometimes from what I see, what I hear, what I read. It can start in the shower, when I am cooking or while I lie on the bed waiting to fall asleep. I can spend long months without writing anything. Things first need to boil. I need to find myself in a position where I can no longer bracket the interpellation addressed to me by reality, an event or an encounter.

Do you take notes?

Not really, or not all the time. I may have notebooks, but I keep misplacing them and hardly ever return to them in any structured way. My writing generally begins with a word, a concept, a sound, a landscape or an event which suddenly resonates in me. I do have a very lively mental scape. As a result, writing is like translating an image into words. In fact my books are full of images of the mind, non-visual images. But I never know in advance where these images will lead me to or whether at the end of the process I will be able to adequately translate them into words without losing their allure. It’s a rather intuitive process. That’s also why I write my introductions at the end, as I’ll only be able to tell you what the book is about once it’s written, when all the images have been curated.

Do you spend lots of time rewriting your sentences?

I’m extremely attentive to each word, each phrase, the way it’s formulated, its rhythm and musicality, the punctuation. For a text to be powerful, that is to heal, it must viscerally speak to both the reader’s reason and senses. It must therefore be methodically composed, arranged, and curated. Once it’s done with the appropriate amount of care, I no longer go back to it. I actually never reread my books.

Why ?

Because I’m always afraid to realize that the translation of images into words could have been done differently, and that now it’s too late. It’s already published and now belongs somewhat to the public. I have a rather strange understanding of writing. Writing is like a trial with too many judges If one doesn’t wish to be condemned, one shouldn’t write. Because once you’ve written and published something, that’s it.. The door is locked and the key is taken away. Writing is like pronouncing a sentence on oneself.

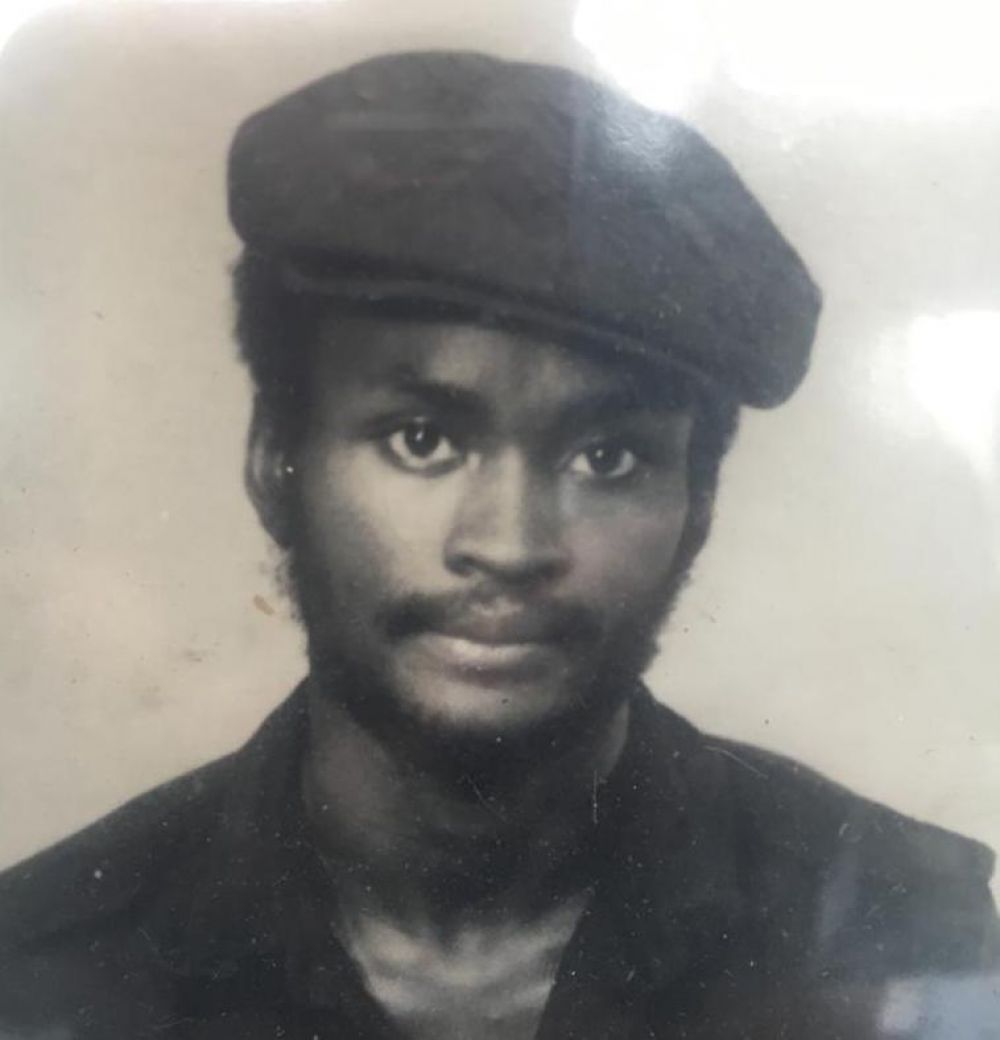

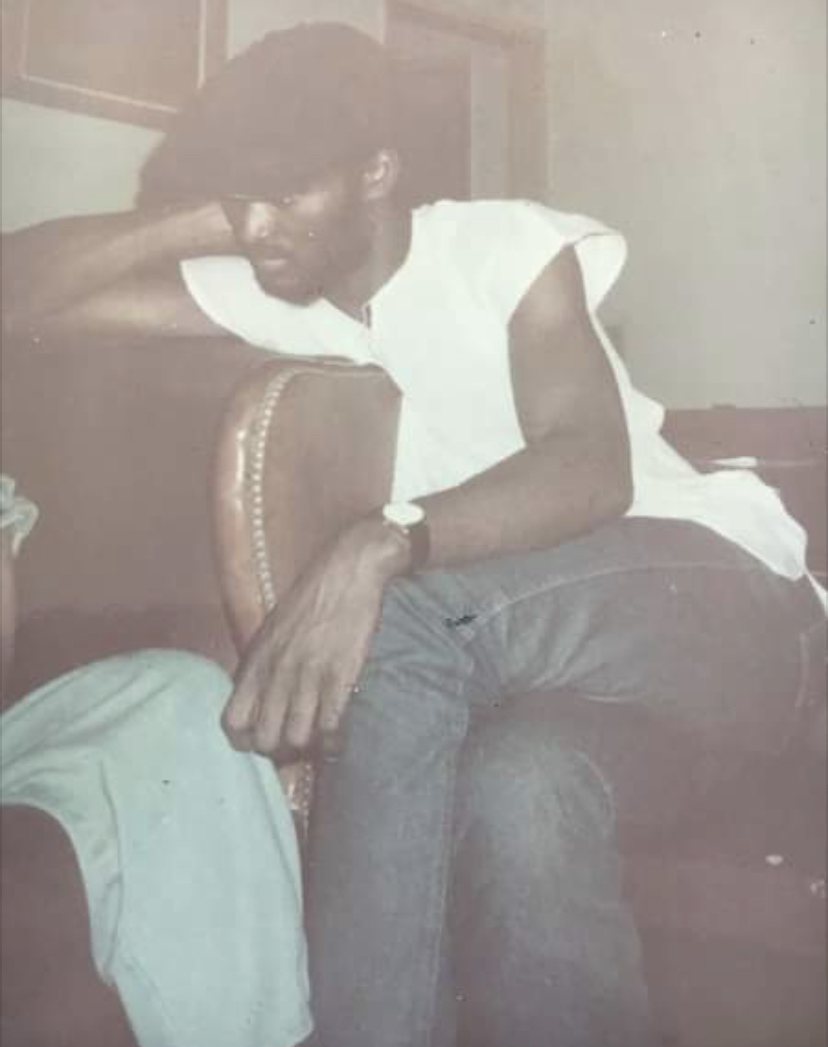

Student in Paris in the 1980

Student in Paris in the 1980

You spend a significant amount of your time playing and watching soccer. What is it that you enjoy so much in this sport?

It’s all about contingency and creation, creating in the midst of contingency. It’s about a certain relationship between a body in motion and a mind in a state of alert. That’s what fascinates me the most about football, the way in which 22 people attempt to inhabit a space they keep configuring and reconfiguring, erecting and erasing, and the explosions of primal joy when one’s team scores, or the primal screams when one’s team loses. And indeed, if I could go back in time, I would unquestionably pursue a professional soccer career. I’d retire in my early thirties and then do something else.

If you were a philanthropic billionaire, in which cause would you invest?

I’ve always considered money as a means to hinder one’s freedom.

Why?

I don’t want to be the slave of anything or of anybody. Not even the slave of my own passions.

Doesn’t money enable a certain freedom too?

If I had billions, I’d go back to Cameroun and revive my father’s farm. That’s where I spent part of my youth. I’d go back and turn this farm into a cooperative, into a laboratory for new ways of producing and living. The farm would become a living alternative of how to use local resources to live a clean life, starting with air, water, plants, food and so on. The farm would also be a vibrant place for artistic innovation. It would offer writing residencies for authors eager to commune with the vast expanses of our universe.

If you could reincarnate, choose an era, country, profession, legend, what or whom would you choose?

I’d come back as Ibn Khaldun, an Arab intellectual who is often presented as one of the very first sociologists. He visited the empire of Mali in the 14th century. I would be curious to discover this era. To be a sort of intellectual who travels the world, discovering Africa before the Triangular trade and sounding out what we could have become.

***